Traceamine

Trace amines (TAs) are endogenous biogenic amines and closely related to biogenic amine neurotransmitters.1 They are formed by decarboxylation of aromatic amino acids and occur in vertebrates only in small quantities (order of magnitude 1/100 of the corresponding neurotransmitters). In invertebrates, however, they are common and are involved in an equivalent of the mammalian adrenergic system and the fight-and-flight response. Invertebrates do not possess TAAR.2

Trace amines are involved in the regulation of dopamine, glutamate and serotonin neurotransmitter metabolism in the brain.2

In high concentrations, they have a similar effect to amphetamines at the presynapse on the release, reuptake and biosynthesis of catecholamines and indolamines. In low concentrations, they show modulating effects at the postsynapse, which increase the activity of other neurotransmitters, especially dopamine and serotonin.3

- 1. Traceamine

- 2. Trace amine receptors

- 3. Degradation of trace amines

- 4. Interaction dopamine system / trace amine system

- 5. Trace amines and ADHD

1. Traceamine

1.1. Dopamine-related trace amines

- Β-Phenylethylamine

- N-methylphenylethylamine

- Secondary trace amine

- N-methylphenylethylamine derivatives, which can partially cross the brain-blood barrier, are found in Ginkgo biloba extracts4

- P-Tyramine

- N-methylptryramine

- Secondary trace amine

- 3-Methoxytyramine

- Dopamine metabolite

1.2. Noradrenaline-related trace amines

- Octopamine

- Synephrine

- Secondary trace amine

1.3. Serotonin-related trace amines

- Tryptamine

- N-methylptryptamine

- Secondary trace amine

1.4. TAAR agonists

- 3-Methoxytyramine (3-MT)5

- Catecholamine neurotransmitter metabolite

- Main metabolite of dopamine in the extracellular space

- Normetanephrine6

- Catecholamine neurotransmitter metabolite

- Dimethylethylamine (DMEA)7

- Trimethylamine7

- Catecholamine neurotransmitter metabolite

- Isoamylamine8

- Catecholamine neurotransmitter metabolite

- In particular on mTAAR3 (mouse TAAR-3)

- 3-Iodothyronamine (3IT)9

- An endogenous thyroid hormone metabolite

- Putrescine10

- Polyamine

- Cadaverine10

- Polyamine

- Possibly agmatine, spermine and spermidine2

- N-methylphenylethylamine1

- N-methylated metabolites of PEA

- N-methyltyramine11

- N-methylated metabolites of TYR

- N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)2

- N-methyl metabolite of TRP

- Dopamine

- Serotonin

1.5. Sources of trace amines

Matured cheeses, fermented meats, red wine, soy products and chocolate have been shown to be enriched with one or more of the aromatic amino acids PEA, TYR and TRP. Seafood showed high levels of gmatine, cadaverine, OCT, PEA, putrescine, spermidine, spermine, TRP and TYR.2 Tofu also contains high levels of aromatic amino acids.12 However, aromatic amino acids in food barely reach the concentration to bind hTAAR, with the exception of hTAAR1 and hTAAR9 in the stomach.12

- Decarboxylation of aromatic amino acids occurs in different cell types, so that trace amines can theoretically be formed in these:2

- Nerve cells

- Glial cells

- Blood vessels

- Cells of the gastrointestinal tract

- Kidney

- Liver

- Lung

- Stomach

- Serotonergic AADC, especially in the pylorus12

Cells that can produce trace amines by means of aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) were found in the following areas of the brain:13

- Raphe nuclei (serotonergic, very strong AADC)

- Pons ventral (serotonergic, very strong AADC)

- Medulla ventral (serotonergic, very strong AADC)

- Mesencephalic reticular formation (dopaminergic, moderate to strong AADC)

- Substantia nigra (dopaminergic, moderate to strong AADC)

- VTA (domapinergic, moderate to strong AADC)

- Locus coeruleus (noradrenergic, moderate to strong AADC)

- Subcoeruleus nuclei (noradrenergic, moderate to strong AADC)

- Median and ventrolateral parts of the intermediate reticular nucleus in the medulla oblongata (noradrenergic / adrenergic, moderate AADC)

- Forebrain: few non-aminergic AADC-positive neurons (D-neurons); these were not detectable in other parts of the human brain.

The enzyme aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase encoded by the AADC gene occurs in different forms, which cause dopaminergic and serotonergic decarboxylase:

- Dopaminergic: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine decarboxylase

- Serotonerg: 5-hydroxytryptophan decarboxylase

1.6. Regulation of the AADC

The aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC), by means of which trace amines are produced from precursors, is itself subject to regulatory influences:

- PH value changes14

- Denaturation14

- Destruction of dopaminergic cells only reduced the dopaminergic 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine decarboxylase, not the serotonergic 5-hydroxytryptophan decarboxylase activity, which actually increased.15 In contrast, another study found that the destruction of both dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons reduced both dopaminergic and serotonergic AADC equally.16

- The serotonergic 5-hydroxytryptophan decarboxylase activity and the dopaminergic 3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine decarboxylase showed divergent activity maxima depending on pH, temperature and substrate concentrations:17

- The serotonergic AADC activity:

- Dopaminergic AADC activity:

1.7. Storage of trace amines

Unlike dopamine and noradrenaline, trace amines are not stored in synaptic vesicles. They diffuse from the nerve cell directly and easily through the plasma membranes.2

2. Trace amine receptors

Trace amine receptors (since 2005: TAAR, Trace amine associated receptor) have been found in the nucleus accumbens and substantia nigra. These are predominantly G-protein-coupled receptors, which therefore increase cAMP when binding to trace amines.

While other animals can have more TAAR (fish have over 100), humans have more than hTAAR:

hTAARs are functional receptors controlled by their own genes, with the exception of hTAAR3, -4 and -7, which are encoded by pseudogenes. In addition, there are said to be hundreds of orphan hTAARs12

2.1. HTAAR1 (TA-1, TAR-1, TRAR-1)

TAAR1 is most frequently found in the amygdala in the brains of both mice and humans.

TAAR1 are predominantly localized intracellularly, which enables presynaptic and postsynaptic effects2

2.1.1. TAAR1 agonists

- Attachment affinity:

- Tyramine > β-phenylethylamine > dopamine = octopamine19

- Β-PEA > tyramine > tryptamine > synephrine > dopamine > octopamine > serotonin > histamine > noradrenaline20.

- S(+)-Amfetamine >> P-Hydroxymethamphetamine > R(-)-Amfetamine > (+)-Methamphetamine > R(-)-Apomorphine >> 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline > Selegiline > d-LSD > Haloperidol > Chlorpromazine > Phencyclidine > Fluoxetine > Cocaine > Pargyline, Promazine, Clozapine, Risperidone, Clorgyline20.

- Tyramine (TYR)19

- Β-Phenylethylamine (PEA)19

- Dopamine (DA)21

- Octopamine (OCT)19

- Amfetamine (AMP)622

- Methylphenidate (MPH) is not a TAAR-1 agonist, but could indirectly activate it by blocking the transport of trace amines through monoamine transporters or orphan transporters.22

- 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamfetamine (MDMA)622

- Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD)622

- Ergoline derivatives622

- Ractopamine23, an additive in cattle feed for pigs, cattle and turkeys in the USA (not uncritically viewed there and increasingly rarely used); banned in the EU and Russia

- L-isoleucine could be a TAAR1 ligand

- Isoleucine is an amino acid that crosses the blood-brain barrier and is found particularly in poultry, meat, pulses and cheese.

- Phenylethanolamine appears to be a weak TAAR1 ligand2

- Mephedrone24

- Cathinone derivative

- Weak TAAR1 agonist

- Methylenedioxypyrovalerone24

- Cathinone derivative

- Weak TAAR1 agonist

- Some monoamine transporters appear to support the activation of TAAR-1

- Dopamine transporter (DAT)21

- Noradrenaline transporter (NET)21

- Serotonin transporter (SERT)21

- D2 autoreceptors appear to inhibit TAAR-121

- In the body, TAAR1 regulates nutrient-induced hormone secretion, making TAAR1 a potential therapeutic target in diabetes and obesity2

- TAAR1 can regulate immune responses by controlling the differentiation and activation of leukocytes.2

Effect of TAAR agonists.

The selective TAAR1 partial agonist RO5203648 has an antipsychotic, antidepressant and somewhat anxiolytic effect. It increased dopamine in the VTA and serotonin in the raphe nuclei. RO5203648 attenuated addictive behavior and significantly promoted attention, cognitive performance and alertness.25

The selective TAAR1 agonist RO5166017 inhibited the firing frequency of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA and serotonergic neurons in the raphe nuclei. The firing frequency of noradrenergic neurons in the locus coeruleus remained unchanged. RO5166017 altered the desensitization rate and agonist potency at 5-HT(1A) receptors in the dorsal raphe nuclei. RO5166017 reduced stress-induced hyperthermia by acting at TAAR1. RO5166017 reduced dopamine-dependent hyperactivity in cocaine-treated, DAT-KO and NMDA antagonist-treated mice.26

The partial TAAR1 agonist RO5263397 reduced intravenous self-administration of METH in rodents with chronic exposure to psychostimulants.27

2.1.2. TAAR1 antagonists

EPPTB (N-(3-ethoxy-phenyl)-4-pyrrolidin-1-yl-3-trifluoromethyl-benzamide)28

2.1.3. Occurrence of TAAR1

- Hypothalamus29

- Preoptical area29

- VTA29

- Amygdala29

- Dorsal raphe nucleus29

- Nucleus tractus solitarii29

- Parahippocampal area (rhinal cortices)29

- Nucleus tractus solitaire29

- Subiculum29

- Not in

- HTAAR1 (also) occurs in the stomach, particularly in the pylorus12

2.1.4. TAAR1 and the dopaminergic system

Trace amines and dopamine show complex interactions. TAAR1 regulate dopamine, which is associated with the high expression of TAAR1 in VTA and substantia nigra.2

- The trace amines β-PEA and TYR are synthesized in dopaminergic terminals but not stored in vesicles. β-PEA and TYR diffuse easily through plasma membranes.

- Β-PEA and TYR recovery takes place via OCT2

- D2R presynaptic inhibits PEA/TYR synthesis.

- The degradation of dopamine by COMT generates 3-MT (TAAR1 agonist).

- Extracellular 3-M, extracellular PEA and extracellular TYR are agonists of the TAAR1/D2R heteromer complex both presynaptically and postsynaptically.

- Dopamine appears to induce c-FOS luciferase expression via TAAR1, but only in the presence of DAT21

- TAAR1 agonists reduce the firing rate of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA28

2.2. HTAAR2 (GPR58)

2.3. HTAAR3 (GPR57P)

2.4. HTAAR4 (TA2, TA2P, 5-HT4P)

2.5. HTAAR5 (PNR)

Agonists of hTAAR5:

- Dimethylethylamine (DMEA)7

- Trimethylamine (TRA)7

- Do not bind to hTAAR5:7

- Dimethylamine

- Methylamine

- Trimethylphosphine

- Cyclohexylamine

- N-methylpiperidine

- Pyridine

- Β-Phenylethylamine

- Skatol

- Ethanolamine

- Putrescine

- Isobutylamines

- Dimethylbutylamine

2.6. HTAAR6 (TA4, TRAR4)

TAAR-630

* Is associated with schizophrenia and bipolar Disorder in humans

* Not G-protein-coupled

* Does not bind to monoamines (unlike TAAR-1)

* Does not occur in monoaminergic brain regions in rhesus monkeys

2.7. HTAAR7 (TA12, TAAR7a and others)

Other earlier designations and isoforms are TA15 (TAAR7d), TA14 (TAAR7e), TA13P (TAAR7f), TA9 (TAAR 7g), TA6 (TAAR7h).2

2.8. HTAAR8 (TA5, TRAR5, TAR5, GPR102)

Other earlier designations and isoforms are TA11 (TAAR8a), TA7 (TAAR8b), TA10 (TAAR8c).2

2.9. HTAAR9 (TA3, TRAR3, TAR3)

3. Degradation of trace amines

3.1. Resumption

It is possible that PEA is resumed by the OCT2 transporter.31

If this proves to be the case, this would provide an approach for drug interventions.

3.1. Metabolization

Trace amines are primarily broken down via MAO-A and MAO-B,32 and semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO; also known as vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) amine oxidase, copper containing 3 (AOC3)). Catabolization via cytochrome P450 seems possible, but is of secondary importance.2

4. Interaction dopamine system / trace amine system

The dopamine system and the TAAR1 system interact in complex ways:233

- TAAR1 is a dopamine and amphetamine receptor that interacts with DAT and D2 receptors. TAAR1 plays an important role in regulating the addiction-related effects of stimulants34 and the dopaminergic system35

- TAAR1 can migrate to the cell surface after heterodimerization with D2R, an effect that promotes D2R signaling, although this occurs through the Gi signal transduction cascade rather than the β-arrestin-2 pathway.

- Presynaptic D2R activation via the Gi signal transduction cascade leads to inhibition of PEA/TYR synthesis.

- Dopamine is degraded extracellularly by COMT to 3-MT. 3-MT is a TAAR-1 agonist which, like extracellular PEA and TYR, can activate the TAAR1/D2R heteromer complex at both pre- and postsynaptic membranes.

- There are no interactions between D1R and TAAR1.

The TAAR1 ligands PEA and TYR show indirect sympathomimetic effects similar to those of amphetamine,3637 38 e.g. reuptake inhibition and displacement of monoamine neurotransmitters from the vesicles. However, this only occurs at very high levels of at least 10 µM (probably 100 times the usual physiological concentrations)3339 40 or when extremely high doses of more than 25 mg/kg) PEA/TYR are administered.41

Octapamine shows similar indirect sympathomimetic reactions42

Various amphetamine derivatives bind to TAAR1, see above.

Unlike amphetamine (and other drugs), PEA does not trigger a conditioned taste aversion reaction.43

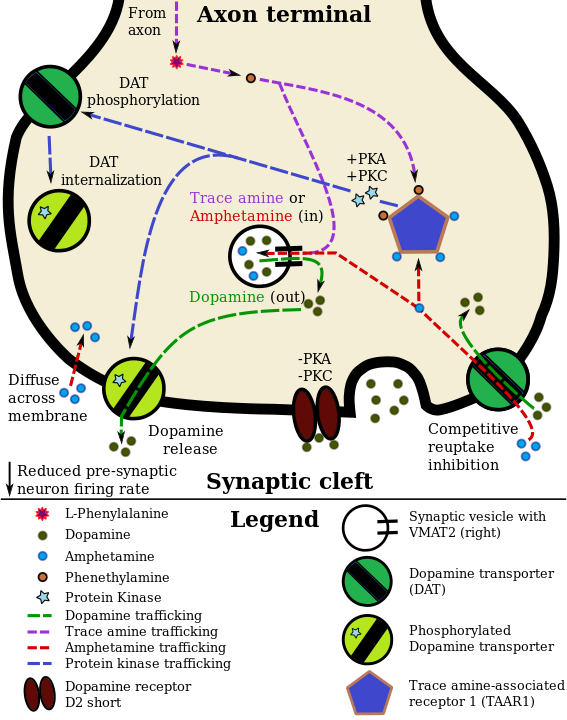

Graphic from Wikipedia: Dopamine

By Seppi333 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=31186161

Illustration of a dopamine neuron with a colocalized TAAR1 receptor and the effects of a TAAR1 agonist (amphetamine or a trace amine such as phenethylamine) on dopamine reuptake and efflux: Amphetamine enters the presynaptic neuron via membrane or DAT. There it binds to TAAR1 or enters the vesicles via VMAT2. When amphetamine or a trace amine binds to TAAR1, it reduces the firing rate of postsynaptic dopamine neurons (via mechanisms not shown) and triggers signaling by protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC), leading to DAT phosphorylation. The phosphorylated DAT then either releases dopamine (efflux) or retracts into the presynaptic neuron and ceases transport. When amphetamine or a trace amine enters the synaptic vesicles via VMAT2, dopamine is released into the cytosol (light brown area).444546

5. Trace amines and ADHD

Endogenous trace amines have been associated with ADHD since the mid-1980s.

Some studies found significantly reduced levels of β-phenethylamine (PEA), phenylacetyl acid (PAA), phenylanaline and P-tyrosine in the urine of children with ADHD or ASD, as well as PAA, phenylanaline and tyramine in plasma 47 4849 32

MPH such as AMP normalize urinary PEA concentrations in boys with ADHD.49

Another small study found elevated tryptophan blood levels in ADHD-HI correlated with hyperactivity.50

A very small study found in ADHD:51

- 4-pyridoxic acid (4PA) / tryptophan (TRP) ratio reduced

- Indoxyl sulphate (IND) / tryptophan (TRP) ratio reduced

- Indoxyl sulfate (IND) / kynurenine (KYN) ratio reduced

- TRP (tryptophan) tripled

- KYN (kynurenine) more than doubled

- 3-HOKYN (3-hydroxykynurenine) more than doubled

- 3-HOKYN is toxic.

- KA (kynurenic acid) strongly increased

- IND (indoxyl sulfate) reduced

which indicates a dramatically impaired activity of the pyridoxine-dependent enzymes and an inborn error of B6 metabolism (as in epilepsy). The KYN / TRP ratio represents an index of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity, the enzyme that limits tryptophan degradation. The 3-HOAA/3-HOKYN ratio is an index of kynureninase activity. MPH appears to increase kynurenic acid and decrease quinolinic acid in plasma in ADHD. MPH did not alter TRP degradation, but created a kind of equilibrium between some of the metabolites detected, but not in the 4PA/TRP, IND/TRP or IND/KYN ratio. Long-term treatment with pyridoxine normalized ADHD symptoms without serious side effects.51

Another study found no significant abnormalities of tryptophan, tyrosine or phenylalanine in children with ADHD, even though decreased blood levels of these substances tended to correlate with ADHD.52

A meta-analysis found in ADHD:53

- higher kynurenine levels (SMD = 0.56), also in drug-naïve children with ADHD (SMD = 0.74)

- reduced kynurenic acid levels (SMD = -0.33), also in drug-naïve children with ADHD (SMD = -0.37)

- increased tryptophan levels in drug-naïve children with ADHD (SMD = 0.31)

Lindemann, Hoener (2005): A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005 May;26(5):274-81. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID: 15860375. REVIEW ↥ ↥

Gainetdinov, Hoener, Berry (2018): Trace Amines and Their Receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2018 Jul;70(3):549-620. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.015305. PMID: 29941461. REVIEW ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

Burchett, Hicks (2006): The mysterious trace amines: protean neuromodulators of synaptic transmission in mammalian brain. Prog Neurobiol. 2006 Aug;79(5-6):223-46. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2006.07.003. PMID: 16962229. REVIEW ↥

Könczöl Á, Rendes K, Dékány M, Müller J, Riethmüller E, Balogh GT. Blood-brain barrier specific permeability assay reveals N-methylated tyramine derivatives in standardised leaf extracts and herbal products of Ginkgo biloba. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016 Nov 30;131:167-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2016.08.032. Epub 2016 Aug 29. PMID: 27592255. ↥

Sotnikova, Beaulieu, Espinoza, Masri, Zhang, Salahpour, Barak, Caron, Gainetdinov (2010): The dopamine metabolite 3-methoxytyramine is a neuromodulator. PLoS One. 2010 Oct 18;5(10):e13452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013452. Erratum in: PLoS One. 2010;5(10) doi: 10.1371/annotation/a2019934-b1cc-4781-80cb-9e09fc7ff6dc. PMID: 20976142; PMCID: PMC2956650. ↥

Bunzow, Sonders, Arttamangkul, Harrison, Zhang, Quigley, Darland, Suchland, Pasumamula, Kennedy, Olson, Magenis, Amara, Grandy (2001): Amphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, lysergic acid diethylamide, and metabolites of the catecholamine neurotransmitters are agonists of a rat trace amine receptor. Mol Pharmacol. 2001 Dec;60(6):1181-8. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.6.1181. PMID: 11723224. ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

[Wallrabenstein, Kuklan, Weber, Zborala, Werner, Altmüller, Becker, Schmidt, Hatt, Hummel, Gisselmann \(2013\): Human trace amine-associated receptor TAAR5 can be activated by trimethylamine. PLoS One. 2013;8\(2\):e54950. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054950. PMID: 23393561; PMCID: PMC3564852.](https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12479782/) ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

Ferrero, Wacker, Roque, Baldwin, Stevens, Liberles (2012): Agonists for 13 trace amine-associated receptors provide insight into the molecular basis of odor selectivity. ACS Chem Biol. 2012 Jul 20;7(7):1184-9. doi: 10.1021/cb300111e. Epub 2012 May 7. PMID: 22545963; PMCID: PMC3401279. ↥

Scanlan, Suchland, Hart, Chiellini, Huang, Kruzich, Frascarelli, Crossley, Bunzow, Ronca-Testoni, Lin, Hatton, Zucchi, Grandy (2004): 3-Iodothyronamine is an endogenous and rapid-acting derivative of thyroid hormone. Nat Med. 2004 Jun;10(6):638-42. doi: 10.1038/nm1051. PMID: 15146179. ↥

Hussain, Saraiva, Ferrero, Ahuja, Krishna, Liberles, Korsching (2013): High-affinity olfactory receptor for the death-associated odor cadaverine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013 Nov 26;110(48):19579-84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1318596110. PMID: 24218586; PMCID: PMC3845148. ↥ ↥

(Lindemann, Hoener (2005): A renaissance in trace amines inspired by a novel GPCR family. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005 May;26(5):274-81. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.03.007. PMID: 15860375. REVIEW ↥

Ohta, Takebe, Murakami, Takahama, Morimura (2017): Tyramine and β-phenylethylamine, from fermented food products, as agonists for the human trace amine-associated receptor 1 (hTAAR1) in the stomach. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2017 May;81(5):1002-1006. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2016.1274640. PMID: 28084165. ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

Kitahama K, Ikemoto K, Jouvet A, Araneda S, Nagatsu I, Raynaud B, Nishimura A, Nishi K, Niwa S. Aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase-immunoreactive structures in human midbrain, pons, and medulla. J Chem Neuroanat. 2009 Oct;38(2):130-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.06.010. PMID: 19589383. ↥

Bender, Coulson (1972): Variations in aromatic amino acid decarboxylase activity towards DOPA and 5-hydroxytryptophan caused by pH changes and denaturation. J Neurochem. 1972 Dec;19(12):2801-10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1972.tb03817.x. PMID: 4652630. ↥ ↥

Sims, Bloom (1973): Rat brain L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine and L-5-hydroxytryptophan decarboxylase activities: differential effect of 6-hydroxydopamine. Brain Res. 1973 Jan 15;49(1):165-75. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(73)90408-3. PMID: 4540548. ↥

Dairman, Horst, Marchelle, Bautz (1975): The proportionate loss of L-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine and L-5-hydroxttryptophan decarboxylating activity in rat central nervous system following intracisternal administration of 5, 6-dihydroxytryptamine or 6-hydroxydopamine. J Neurochem. 1975 Apr;24(4):619-23. PMID: 1079044. ↥

Sims, Davis, Bloom (1973): Activities of 3,4-dihydroxy-L-phenylalanine and 5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan decarboxylases in rat brain: assay characteristics and distribution. J Neurochem. 1973 Feb;20(2):449-64. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1973.tb12144.x. PMID: 4540567. ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

ähnlich: Siow, Dakshinamurti (1985): Effect of pyridoxine deficiency on aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase in adult rat brain. Exp Brain Res. 1985;59(3):575-81. doi: 10.1007/BF00261349. PMID: 3875501. ↥

Borowsky, Adham, Jones, Raddatz, Artymyshyn, Ogozalek, Durkin, Lakhlani, Bonini, Pathirana, Boyle, Pu, Kouranova, Lichtblau, Ochoa, Branchek, Gerald (2001): Trace amines: identification of a family of mammalian G protein-coupled receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001 Jul 31;98(16):8966-71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151105198. PMID: 11459929; PMCID: PMC55357. ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

Wolinsky, Swanson, Smith, Zhong, Borowsky, Seeman, Branchek, Gerald (2007): The Trace Amine 1 receptor knockout mouse: an animal model with relevance to schizophrenia. Genes Brain Behav. 2007 Oct;6(7):628-39. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00292.x. PMID: 17212650. ↥ ↥

Xie, Westmoreland, Bahn, Chen, Yang, Vallender, Yao, Madras, Miller (2007): Rhesus monkey trace amine-associated receptor 1 signaling: enhancement by monoamine transporters and attenuation by the D2 autoreceptor in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007 Apr;321(1):116-27. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.116863. PMID: 17234900. ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

Miller, Verrico, Jassen, Konar, Yang, Panas, Bahn, Johnson, Madras (2005): Primate trace amine receptor 1 modulation by the dopamine transporter. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005 Jun;313(3):983-94. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.084459. PMID: 15764732. ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

Liu, Grandy, Janowsky (2014): Ractopamine, a livestock feed additive, is a full agonist at trace amine-associated receptor 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014 Jul;350(1):124-9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.114.213116. PMID: 24799633; PMCID: PMC4170122. ↥

Simmler, Buchy, Chaboz, Hoener, Liechti (2016): In Vitro Characterization of Psychoactive Substances at Rat, Mouse, and Human Trace Amine-Associated Receptor 1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016 Apr;357(1):134-44. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.229765. PMID: 26791601. ↥ ↥

Revel, Moreau, Gainetdinov, Ferragud, Velázquez-Sánchez, Sotnikova, Morairty, Harmeier, Groebke Zbinden, Norcross, Bradaia, Kilduff, Biemans, Pouzet, Caron, Canales, Wallace, Wettstein, Hoener (2012): Trace amine-associated receptor 1 partial agonism reveals novel paradigm for neuropsychiatric therapeutics. Biol Psychiatry. 2012 Dec 1;72(11):934-42. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.014. PMID: 22705041. ↥

Revel, Moreau, Gainetdinov, Bradaia, Sotnikova, Mory, Durkin, Zbinden, Norcross, Meyer, Metzler, Chaboz, Ozmen, Trube, Pouzet, Bettler, Caron, Wettstein, Hoener (2011): TAAR1 activation modulates monoaminergic neurotransmission, preventing hyperdopaminergic and hypoglutamatergic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 May 17;108(20):8485-90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1103029108. PMID: 21525407; PMCID: PMC3101002. ↥

Thorn, Jing, Qiu, Gancarz-Kausch, Galuska, Dietz, Zhang, Li (2014): Effects of the trace amine-associated receptor 1 agonist RO5263397 on abuse-related effects of cocaine in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014 Sep;39(10):2309-16. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.91. PMID: 24743376; PMCID: PMC4138753. ↥

Bradaia, Trube, Stalder, Norcross, Ozmen, Wettstein, Pinard, Buchy, Gassmann, Hoener, Bettler (2009): The selective antagonist EPPTB reveals TAAR1-mediated regulatory mechanisms in dopaminergic neurons of the mesolimbic system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Nov 24;106(47):20081-6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906522106. PMID: 19892733; PMCID: PMC2785295. ↥ ↥

Lindemann, Meyer, Jeanneau, Bradaia, Ozmen, Bluethmann, Bettler, Wettstein, Borroni, Moreau, Hoener (2008): Trace amine-associated receptor 1 modulates dopaminergic activity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008 Mar;324(3):948-56. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.132647. PMID: 18083911. ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥ ↥

Xie, Vallender, Yu, Kirstein, Yang, Bahn, Westmoreland, Miller (2008): Cloning, expression, and functional analysis of rhesus monkey trace amine-associated receptor 6: evidence for lack of monoaminergic association. J Neurosci Res. 2008 Nov 15;86(15):3435-46. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21783. PMID: 18627029; PMCID: PMC2644554. ↥

Berry, Hart, Pryor, Hunter, Gardiner (2016): Pharmacological characterization of a high-affinity p-tyramine transporter in rat brain synaptosomes. Sci Rep. 2016 Nov 30;6:38006. doi: 10.1038/srep38006. PMID: 27901065; PMCID: PMC5128819. ↥

Branchek, Blackburn (2003): Trace amine receptors as targets for novel therapeutics: legend, myth and fact. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003 Feb;3(1):90-7. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00028-0. PMID: 12550748. REVIEW ↥ ↥

Baker, Raiteri, Bertollini, del Carmine (1976): Interaction of beta-phenethylamine with dopamine and noradrenaline in the central nervous system of the rat. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1976 May;28(5):456-7. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1976.tb04658.x. PMID: 6762. ↥ ↥

Grandy, Miller, Li (2016): “TAARgeting Addiction”–The Alamo Bears Witness to Another Revolution: An Overview of the Plenary Symposium of the 2015 Behavior, Biology and Chemistry Conference. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016 Feb 1;159:9-16. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.11.014. PMID: 26644139; PMCID: PMC4724540. ↥

Miller (2011): The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity. J Neurochem. 2011 Jan;116(2):164-76. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMID: 21073468; PMCID: PMC3005101. ↥

Janssen, Leysen, Megens, Awouters (1999): Does phenylethylamine act as an endogenous amphetamine in some patients? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 1999 Sep;2(3):229-240. doi: 10.1017/S1461145799001522. PMID: 11281991. ↥

Parker, Cubeddu (1988): Comparative effects of amphetamine, phenylethylamine and related drugs on dopamine efflux, dopamine uptake and mazindol binding. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988 Apr;245(1):199-210. PMID: 3129549. ↥

Baud, Arbilla, Cantrill, Scatton, Langer (1985): Trace amines inhibit the electrically evoked release of [3H]acetylcholine from slices of rat striatum in the presence of pargyline: similarities between beta-phenylethylamine and amphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985 Oct;235(1):220-9. PMID: 3930699. ↥

Raiteri, Del Carmine, Bertollini, Levi (1977): Effect of sympathomimetic amines on the synaptosomal transport of noradrenaline, dopamine and 5-hydroxytryptamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 1977 Jan 21;41(2):133-43. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(77)90202-3. PMID: 832672. ↥

Berry (2004): Mammalian central nervous system trace amines. Pharmacologic amphetamines, physiologic neuromodulators. J Neurochem. 2004 Jul;90(2):257-71. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02501.x. PMID: 15228583. ↥

Dourish (1982): An observational analysis of the behavioural effects of beta-phenylethylamine in isolated and grouped mice. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 1982;6(2):143-58. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5846(82)80190-5. PMID: 7202236. ↥

Parker, Cubeddu (1988): Comparative effects of amphetamine, phenylethylamine and related drugs on dopamine efflux, dopamine uptake and mazindol binding. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1988 Apr;245(1):199-210. PMID: 3129549. ↥

Greenshaw, Turrkish, Davis (2002): The enigma of conditioned taste aversion learning: stimulus properties of 2-phenylethylamine derivatives. Physiol Res. 2002;51 Suppl 1:S13-20. PMID: 12479782. ↥

Wimalasena K (2011): Vesicular monoamine transporters: structure-function, pharmacology, and medicinal chemistry. Med Res Rev. 2011 Jul;31(4):483-519. doi: 10.1002/med.20187. PMID: 20135628; PMCID: PMC3019297. REVIEW ↥

Miller GM (2011): The emerging role of trace amine-associated receptor 1 in the functional regulation of monoamine transporters and dopaminergic activity. J Neurochem. 2011 Jan;116(2):164-76. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07109.x. PMID: 21073468; PMCID: PMC3005101. REVIEW ↥

Eiden LE, Weihe E (2011): VMAT2: a dynamic regulator of brain monoaminergic neuronal function interacting with drugs of abuse. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 Jan;1216:86-98. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05906.x. PMID: 21272013; PMCID: PMC4183197. REVIEW ↥

Kusaga (2002): [Decreased beta-phenylethylamine in urine of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and autistic disorder]. No To Hattatsu. 2002 May;34(3):243-8. Japanese. PMID: 12030014. ↥

Baker, Bornstein, Rouget, Ashton, van Muyden, Coutts (1991): Phenylethylaminergic mechanisms in attention-deficit disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1991 Jan 1;29(1):15-22. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(91)90207-3. PMID: 2001444. ↥

Zametkin, Brown, Karoum, Rapoport, Langer, Chuang, Wyatt (1984): Urinary phenethylamine response to d-amphetamine in 12 boys with attention deficit disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1984 Sep;141(9):1055-8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.9.1055. PMID: 6380319. ↥ ↥

Hoshino Y, Ohno Y, Yamamoto T, Kaneko M, Kumashiro H (1985): Plasma free tryptophan concentration in children with attention deficit disorder. Folia Psychiatr Neurol Jpn. 1985;39(4):531-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1985.tb00807.x. PMID: 3833631. n = 22 ↥

Dolina, Margalit, Malitsky, Rabinkov (2014): Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a pyridoxine-dependent condition: urinary diagnostic biomarkers. Med Hypotheses. 2014 Jan;82(1):111-6. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2013.11.018. PMID: 24321736. n = 64 ↥ ↥

Bergwerff, Luman, Blom, Oosterlaan (2016): No Tryptophan, Tyrosine and Phenylalanine Abnormalities in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. PLoS One. 2016 Mar 3;11(3):e0151100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151100. PMID: 26938936; PMCID: PMC4777504. n = 155 ↥

Cavaleri D, Crocamo C, Morello P, Bartoli F, Carrà G (2024): The Kynurenine Pathway in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Blood Concentrations of Tryptophan and Its Catabolites. J Clin Med. 2024 Jan 19;13(2):583. doi: 10.3390/jcm13020583. PMID: 38276089; PMCID: PMC10815986. ↥