Amfetamine medication (AMP) for ADHD

Due to the responder/non-responder profile, which differs from MPH, amfetamine medication is particularly suitable for people with ADHD who do not respond to MPH, regardless of age, and clearly before the use of non-stimulants (e.g. noradrenergic medication or tricyclic antidepressants).1 A summary of several studies reports a 69% response rate to amfetamine medication and a 59% response rate to methylphenidate. 87 % of people with ADHD responded to one of the two types of medication.2

Amfetamine medication is also suitable - (even) better than MPH - for the co-treatment of comorbid dysphoria or depression. More on this under Stimulant monotherapy as a first step in comorbid depression and ADHD] In the article Choice of medication for ADHD or ADHD with comorbidity.

In December 2025, we replaced the outdated spelling Amphetamine with the modern spelling Amfetamine.

- 1. Active ingredients of amfetamine drugs

- 2. Authorization and prescription of amfetamine drugs

- 3. Effect of amfetamine medication

- 3.1. Dopamine with amfetamine medication

- 3.1.1. Effect on DAT

- 3.1.2. Vesicular release

- 3.1.3. D2 autoreceptor activation

- 3.1.4. Increase in tyrosine hydroxylase

- 3.1.5. Increased DA firing / activation in dopaminergic brain regions

- 3.1.6. Reduced DA firing in the nucleus accumbens

- 3.1.7. Extracellular DA in the striatum increased more than by MPH

- 3.1.8. Synaptic DA binding reduced by AMP in the same way as by MPH

- 3.1.9. DA influence indirectly via effects on dopamine cells emanating from other brain regions

- 3.1.10. Downregulation of dopamine receptors?

- 3.2. Noradrenaline with amfetamine medication

- 3.3. Monoamine

- 3.4. Serotonin

- 3.5. Effect on the HPA axis

- 3.6. Inhibition of OCT2

- 3.7. Other effects on brain functions

- 3.8. Overview of AMP and neurotransmitters

- 3.1. Dopamine with amfetamine medication

- 4. Effect of amfetamine medication compared to MPH / atomoxetine

- 5. Effect on ADHD symptoms

- 6. Response rate (responding / non-responding)

- 7. No gender-specific differences in effectiveness

- 8. Calming effect at low doses, activating at high doses

- 9. Dosage of amfetamine medication or MPH

- 10. Effect profile (temporal) / duration of action

- 11. Areas of application of amfetamine medication in relation to MPH

- 12. Side effects

- 13. Degradation of amfetamine

- 13.1. Degradation of LDX to d-AMP

- 13.2. Degradation of D-AMP and L-AMP

- 14. Contraindications and interactions

- 15. Long-term effect: No habituation effects of amfetamine medication

- 16. Preparations

- 17. Taking amfetamine medication abroad

1. Active ingredients of amfetamine drugs

AMP has a chiral center with two enantiomers:3

- Levo-AMP (l-AMP)

- Noradrenaline release as strong as or stronger than d-AMP

- Dextro-AMP (d-AMP)

- higher dopamine release than l-AMP

Around 1976 it became known that a mixture of L-Amp and D-Amp worked better than D-Amp, which had been used on its own until then4

The d-isomer is four times more effective at releasing dopamine than the l-isomer, while noradrenaline is released equally by both isomers or even slightly more by l-amfetamine4

The amfetamine mixed salt preparations available in the USA, which consist of equal parts racemic d,l-AMP sulfate, d,l-AMP aspartate monohydrate and two enantiomeric pure d-AMP salts (d-AMP sulfate and d-AMP saccharate), resulting in a ratio of 3:1 between d-AMP and l-AMP isomers and salts, a relatively greater release of noradrenaline than pure d-AMP, but still a greater release of dopamine than noradrenaline in absolute terms.

The following are relevant for the treatment of ADHD:

1.1. Dextroamfetamine (D-Amfetamine)

Dextroamfetamine (the right-turning isomer = dextrorotatory) is also called dexamfetamine or S-(+)-amfetamine.

Dextroamfetamine is the dextrorotatory (D-)enantiomer of amfetamine, as opposed to the levorotatory levoamfetamine (see below).

Dextroamfetamine sulphate is the salt form of dextroamfetamine.

D-amfetamine drugs have a 3 to 4 times stronger effect on the central nervous system than racemic amfetamine drugs, while at the same time having less sympathomimetic effect in the periphery, which is why D-amfetamine drugs are preferred for ADHD treatment.5

D-Amfetamine is only more potent than L-Amfetamine with regard to the dopamine transporters, while the effect on noradrenaline transporters is roughly the same.6

This opens up the possibility of emphasizing dopaminergic (dexamfetamine) or balanced dopaminergic and noradrenergic (levoamfetamine) medication.

D-Amfetamine is more activating than MPH and is therefore preferably recommended for ADHD-I.7

It is also often more effective than MPH for parallel dysthymia / dysphoria / depression due to the noticeable serotonergic effect8.

1.1.1. Dextroamfetamine without lysine binding

Trade name: Attentin (Germany since the end of 2011), Dexamine (Switzerland: as magistral formulation), Dexedrine

Duration of action approx. 6 hours, so that it is usually necessary to take it twice a day.

Increased potential for abuse as no lysine binding.Medice (2017): Attentin® - Guide for prescribing physicians

No approval for adults in Germany, therefore off-label. Reimbursement by health insurance companies is very difficult. Approval for adults has been applied for,

The half-life of the D-enantiomer is9

- for children aged 6 to 12 years 9 hours

- 11 hours for adolescents aged 13 to 17 years

- for adults 10 hours

1.1.2. Dextroamfetamine from lisdexamfetamine (with lysine binding)

Lisdexamfetamine (LDX) is a prodrug of D-amfetamine that is bound to L-lysine to form a substance that is ineffective in itself. Lisdexamfetamine is therefore an active ingredient that is only converted in the body into the actual active substance, in this case D-amfetamine. This means that there is a very low risk of abuse.10 The subjective effect of intravenous administration is identical to that of oral administration, and the Cmax of d-amp is also identical.4 This massively reduces the risk of abuse. Nevertheless, the effect is linear and dose-dependent up to 250 mg. LDX therefore does not offer protection against overdose.11

In its natural L-form, lysine is an essential proteinogenic α-amino acid. The mirror image D-lysine does not occur in natural proteins.

In lisdexamfetamine, the amino group of D-amfetamine is linked to the carbonyl group of L-lysine by an amide bond.

Lisdexamfetamine (LDX) bound to lysine is rapidly absorbed from the small intestine into the bloodstream. This occurs by active transport, presumably by the peptide transporter 1 [PEPT1]. Enzymatic hydrolysis of the peptide bond to release d-amfetamine into the blood occurs in the lysate and in the cytosolic extract of human erythrocytes, but not in the membrane fraction. This conversion is strongly inhibited by a protease inhibitor cocktail, bestatin and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, suggesting an aminopeptidase as the cause of hydrolytic cleavage of the LDX peptide bond. Aminopeptidase B does not appear to be the cause12

Not every prodrug in which an active ingredient with an amide bond is bound to another chemical unit is hydrolyzed in vivo at a predictable rate. There are also derivatives of amfetamines with amide bonds in which the amide bond is not cleaved in vivo (in a useful time).13

Due to the necessary and slow conversion step from LDX to d-AMP, the effect occurs approx. 1 hour later than when taking d-AMP sulphate.11 Unlike LDX, the pharmacologically active d-AMP crosses the blood-brain barrier and enters the CNS, where it exerts its effect.3

Since the effect is quite uniform over the duration of action, the unpleasant rebound effects known from MPH (short-term increased restlessness at the end of the effect) are eliminated or are significantly weaker.

The effect corresponds to D-Amfetamine. A conversion table from dexamfetamine to Vyvanse can be found at ADHSpedia.14 Further conversion tables are available from Kühle15 and for American preparations from Stutzman et al.16

Trade names:

- Vyvanse (EU, since the end of 2013, for children, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 mg)17

- Vyvanse Adult (EU, since 01.05.19, for adults, 30, 50, 70 mg)17. Since 2023, 20, 40 and 60 mg have also been approved in Germany.

- Vyvanse and Vyvanse adult were combined in 2023 to form a single medicine with a single approval. It was already an identical product. Since March 2024, Vyvanse has been available in 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 and 70 mg in Germany for children and adults.

- Vyvanse (USA) is available in doses from 10 mg to 70 mg18

- Tyvense (USA) is available in doses from 20 mg to 70 mg

- Teva-Lisdexamfetamine (Canada) is available in doses of 10 mg, 20 mg, 30 mg, 40 mg, 50 mg, 60 mg and 70 mg19

Generics:

- Since August 2024, lisdexamfetamine has been available in Germany as a generic (e.g. Lisdexamfetamine Ratiopharm), whereby 100-capsule packs are also available on the market.

Lisdexamfetamine has only been classified as a BtM in Germany since 2013.

Austria appears to be the only country in which Vyvanse is not classified as a narcotic (Austrian term: addictive drug), even as of 2023.20

Lisdexamfetamine is also approved in the USA for binge eating.21

Due to its long-lasting effect, dextroamfetamine is subject to steady-state formation. Steady state appears to be reached on day 5.22 Consequences are that when dosing lisdexamfetamine like dextroamfetamine, dosage titrations should not be made below a weekly rhythm.

1.2. Levoamfetamine (L-Amfetamine)

Levoamfetamine (L-amfetamine) is the purely levorotatory isomer of amfetamine. Another name is (-)-amfetamine.

L-amfetamine is less potent than D-amfetamine in terms of dopamine transporters, while the effect on noradrenaline transporters is roughly the same.23 This makes it slightly more noradrenergic than D-amfetamine, but still predominantly dopaminergic.24

L-amfetamine increases blood pressure and pulse rate more than D-amfetamine25

The half-life of the L-enantiomer is9

- for children aged 6 to 12 years 11 hours

- 13 to 14 hours for adolescents aged 13 to 17 years

- for adults 13 hours

We are not aware of any ready-to-use L-amfetamine medication approved in Europe. It would have to be produced on individual prescription in pharmacies.

Equivalents of lisdexamfetamine:

| Lisdexamfetamine | Dextroamfetamine | Dextroamfetamine sulphate |

|---|---|---|

| 10 mg | 2.95 mg | 4.02 mg |

| 20 mg | 5.90 mg | 8.04 mg |

| 30 mg | 8.84 mg | 12.05 mg |

| 40 mg | 11.79 mg | 16.07 mg |

| 50 mg | 14.74 mg | 20.09 mg |

| 60 mg | 17.69 mg | 24.11 mg |

| 70 mg | 20.64 mg | 28.13 mg |

The Lisdexamfetamine to Dextroamfetamine conversion rate is 0.2948.26

The conversion rate of dexamfetamine to dexamfetamine sulphate can be estimated at 1.363.11

1.3. Mixed amfetamine salts / amfetamine derivatives

- Aderall (USA): 75 % dextroamfetamine and 25 % levoamfetamine

* 25 % each of D-amfetamine sulphate, DL-amfetamine sulphate, D-amfetamine accharate and DL-amfetamine aspartate monohydrate

* The different salts are metabolized at different rates, which leads to a slower rise and fall in the blood plasma concentration curve

* Immediate release: Tablet with immediate release of the active ingredient

* Sustained release (Adderall® XR):

* Amfetamine salts in capsule with two types of pellets:

* 50 % with immediate release

* 50% with enteric coating, which first dissolves in the intestine, and thus with a delay, and then releases the amfetamine salt it contains

* Adderall® XR was first approved in the USA in 2001

* Crushing an Adderall® XR tablet removes the retarding effect. All of the amfetamine contained is released immediately. - Evekeo (USA): 50 % dextroamfetamine and 50 % levoamfetamine

Amfetamine mixed salts are a combination of different stimulants:27

D-Amfetamine saccharate

D-Amfetamine sulfate

D,L-Amfetamine sulfate

D,L-Amfetamine aspartate monohydrate

While D,L-amfetamine sulphate mixtures are the most commonly used ADHD medication in the USA, D,L-amfetemine mixtures are only available in a few pharmacies in Germany, which produce them themselves. The production is associated with a waiting time of several weeks. The cost of 180 capsules of 5 mg amfetamine sulphate each was quoted as €200.

1.4. Methamfetamine

- Desoxyn, USA

(1.5. Fenetyllin)

- Captagon (in Germany until 2003; in Belgium until 2010); no longer available today

1.6. Amfetamine derivatives

There are a large number of derivatives of amfetamine. Many are abused as drugs.

Most, but not all, amfetamine derivatives are central stimulants. Fenfluramine and p-chlorobenzphetamine have been shown to have no stimulant effect on the central nervous system.28

The terms amfetamine and amfetamine medication in this article refer to medications with amfetamine as an active ingredient that are still approved today and are used to treat ADHD.

1.7. Historical: Discovery and development of amfetamine

In the 1880s, the chemist Lazăr Edeleanu synthesized amfetamine for the first time. Nagai Nagayoshi extracted ephedrine for the first time from Ephedra spp. used in Chinese traditional medicine and synthesized methamphetamine for the first time in 189329

Ephedrine was available over the counter in Europe and the USA in the 1920s as a decongestant and, due to its bronchodilator and adrenaline-like effect, as a helpful medication for asthma.

in 1927, Gordon Alles synthesized racemic amfetamine and documented that it increased arousal and caused insomnia in humans and animals.

in 1935, Smith, Kline and French Co. marketed amfetamine under the name Benzedrine® for narcolepsy, postencephalitic parkinsonism and depression. Benzedrine was available over the counter as a decongestant inhaler containing a cotton strip soaked in volatile amfetamine oil, which soon led to abuse as a psychostimulant drug.

A few years later, Smith, Kline and French Co. brought the stronger isomer dextroamfetamine onto the market as Dexedrine®.

in 1937, Charles Bradley reported on the positive effect of Benzedrine on children with behavioral problems.

benzedrine and Dexedrine became prescription-only in 1939.

2. Authorization and prescription of amfetamine drugs

2.1. Germany

In Germany, amfetamine medication had to be prepared from raw substances by pharmacists for a long time.30 Since 2011, a D-amfetamine (Attentin) has been available in Germany as a finished drug and approved for the treatment of ADHD (Attentin), and in 2013 a D-amfetamine prodrug (Lisdexamfetamine) was approved for the treatment of children. Lisdexamfetamine contains D-Amp in lysine-bound form (Vyvanse). Since May 2019, Vyvanse Adult has been approved for the treatment of ADHD in adults (30, 50, 70 mg). In 2023, 20, 40 and 60 mg were also approved for adults. Since March 2024, Vyvanse and Vyvanse Adult have been combined to form the drug Vyvanse and are available in 20, 30, 40, 50, 60 and 70 mg in Germany31

In Germany, lisdexamfetamine has been approved as a first-line medication for adults with ADHD since March 2024. It may still only be prescribed for children and adolescents if MPH is not effective enough.32333435363738

The 2017 S3 guideline still pointed out in the long version39 (page 72/198) that lisdexamfetamine could only be used in accordance with approval after prior treatment with MPH, without restricting this statement to children.

Due to the economic efficiency requirement, doctors in Germany are still only allowed to prescribe lisdexamfetamine on prescription if all cheaper medications (methylphenidate, in this case Medikinet before Ritalin adult) were not effective or caused side effects.

Lisdexamfetamine is approved in Germany for adults without age restriction and therefore also for seniors aged 60 and over. Nevertheless, there are no data on the safety and efficacy of lisdexamfetamine in people aged 60 and over. Methylphenidate and all other stimulants must be used off-label from the age of 60.40

2.2. Austria

In Austria, Vyvanse can be prescribed if other medications are ineffective or show side effects. The doctor must justify this to the health insurance company.

2.3. Switzerland

In Switzerland, lisdexamphetamine has been marketed under the brand name Vyvanse® since 2014. Vyvanse® is approved as part of an overall therapeutic strategy for the treatment of ADHD that has persisted since childhood in children aged 6 and over, adolescents and adults. For children aged 6 years and older and adolescents, Vyvanse® may only be used if the response to previously received treatment with methylphenidate is considered clinically inadequate.

Attentin® is approved in Switzerland for the treatment of ADHD in children from the age of six and adolescents up to the age of 18 as part of an overall therapeutic strategy if the clinical response to previous treatment with methylphenidate was inadequate.

2.4. Great Britain

The British NICE guideline (NICE, 2018), which, like the German guideline, is considered by experts to be based on the highest level of scientific evidence, explicitly recommends the use of LDX as a first-line therapy for the treatment of adults with ADHD.41

2.5. USA

Amfetamine medications are available in the USA as:42

- Mixture of D- and L-amfetamine isomers (racemic mixture)

- Mixed sulphates and saccharinates of D- and L-amfetamine isomers (Adderall®)

- Pure D-amfetamine sulphate

- Dexamfetamine hemisulfate (Attentin®, Amfexa®)

- D-Amfetamine as lisdexamfetamine in lysine-bound form (Vyvanse®, Vyvanse®, Tyvense®, generics)

- Racemic methamfetamine sulphate (Desoxyn®, USA)

In the USA, 52.9% of adolescents with ADHD received MPH and 39.3% received amfetamine medication as their first prescribed medication in 2018. Over the course of treatment, MPH is the primary prescribed medication for around 40% and AMP is the primary prescribed medication for 33%.43

3. Effect of amfetamine medication

Amfetamine medication works slightly better in adults than methylphenidate44 and has slightly fewer side effects.

According to the current European consensus, amfetamine medication is the first choice of medication for ADHD in adults (before methylphenidate) and the second choice of medication in children and adolescents (after methylphenidate) 4546

In studies on the effects of amfetamine, it must always be borne in mind that these

- usually use AMP in significantly higher doses than for ADHD medication

- generally use immediate release / not prolonged-acting AMP via prodrug

- frequently inject AMP, which again results in much faster metabolization

- these 3 factors multiply in their effect

There is no doubt that AMP in drug form has a different effect than AMP in drug form.

Amfetamines are closely related in their chemical structure to the catecholamines dopamine and noradrenaline: this explains why they can bind to the receptors and transporters relevant for these. The great similarity between the monoamines also explains why monoamine transporters are relatively less selective, so that the noradrenaline transporter (at least in the PFC) reabsorbs more dopamine than noradrenaline.4

Source: Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (2013): Amphetamine, past and present–a pharmacological and clinical perspective. J Psychopharmacol. 2013 Jun;27(6):479-96. doi: 10.1177/0269881113482532. PMID: 23539642; PMCID: PMC36661944, published under Creative Commons Attribution License

Amfetamine medications have a more complex mechanism of action than methylphenidate.

The description of the effect of amfetamine medication is contradictory. It is sometimes argued that amfetamine drugs merely inhibit dopamine reuptake and release dopamine and noradrenaline. More well-founded accounts from the USA (where amfetamine drugs are prescribed more frequently than in Europe and where there is therefore a more intensive debate about them) cite a reuptake inhibition of dopamine and noradrenaline transporters as the effect and no release of dopamine, noradrenaline or serotonin.

In principle, amfetamine drugs are said to have an intraneuronal effect, while methylphenidate and atomoxetine have an extraneuronal effect.47 As amfetamine drugs also address at least the dopamine transporter and the D2 autoreceptor, this is unlikely to be tenable.

AMP acts primarily in the striatum and further in the cortex and ventral tegmentum.48

The first computer models now exist that can seriously simulate the effect of ADHD drugs. A computer model for the simulation of type 1 diabetes has already been approved by the FDA as a replacement for preclinical animal studies49

A model comparing MPH and AMP in children and adults with ADHD takes into account the effect on 99 proteins involved in ADHD50

3.1. Dopamine with amfetamine medication

The dopamine increase caused by D-amfetamine in PFC is much more pronounced and also much more dose-dependent than with MPH, and is therefore easier to control.47

AMP causes:

- extracellular dopamine levels increased 6-fold51

- tonic dopamine firing enhanced by AMP depleting vesicular stores and promoting non-exocytotic release through reverse transport52

- phasic dopamine firing: contradictory data

- amplified by upregulating vesicular dopamine release52

- Stimulants reduce the phasic release of dopamine51

- AMP promoted the release of dopamine from vesicles by reducing the affinity of vesicles for dopamine uptake (from K(m) 0.8 to K(m) 32). However, the amount of dopamine released per pulse was reduced by 82 % (according to another source by 25 to 50 %). The D2 antagonist sulpiride reduced the inhibition of release, i.e. promoted the release. This was reduced in D2-KO mice. In inhibited D2 autoreceptors, AMP increased the extracellular release of dopamine.53

- AMP reduces vesicular release5455 (this can affect both tonic and phasic release)

3.1.1. Effect on DAT

3.1.1.1. Dopamine (re)uptake inhibition via DAT and NET

Stimulants (MPH such as AMP inhibit dopamine reuptake56 and thus lead (in low doses) to a 6-fold increase in extracellular dopamine levels.51

The increased extracellular dopamine level acts on presynaptic dopamine D2 autoreceptors at the nerve ending. The D2 autoreceptor activation causes a 2- to 3-fold increase in impulse-associated (phasic) dopamine release. This increase is therefore relatively smaller than the increase in extracellular dopamine. The (relatively smaller) increase in phasic dopamine acts on the postsynaptic D2 dopamine receptors and causes reduced locomotor activity. Higher doses of stimulants increase extracellular dopamine more strongly and result in marked behavioral stimulation that cannot be overcome by phasic activation of inhibitory postsynaptic D2 receptors. High D-Amp doses (drugs) cause supersaturation of extracellular postsynaptic D1 and D2 receptors, so that they exceed the inhibitory presynaptic effect of low D-AMP doses.51

- Amfetamine drugs block the dopamine and noradrenaline transporters in a different way to methylphenidate. While the reuptake inhibition of MPH is similar to that of antidepressants, amfetamine drugs act as a competitive inhibitor and pseudosubstrate on dopamine and noradrenaline transporters and bind to the same site where the monoamines bind to the transporter, thereby also inhibiting NE and DA reuptake.57

- Amfetamine is absorbed into the nerve cell through the DAT, whereas MPH is not.58

- D-Amfetamine works

- Dextroamfetamine inhibits dopamine transporters with moderate efficacy (Ki 34-225 nM).60

- Amfetamine can also stabilize dopamine and norepinephrine transporters in channel configurations, reverse efflux through intracellular vesicular monoamine transporters, and cause internalization of dopamine transporters61

D-AMP drug doses cause a D-AMP plasma concentration of around 150 nM, which is sufficient to occupy a significant proportion of the dopamine transporters. This effect coincides with that of MPH.51 - D-amfetamine has approximately three times the affinity for noradrenaline transporters (NET) for reuptake inhibition and two and a half times the affinity for dopamine transporters (DAT) compared to racemic methylphenidate.47 Since there is barely any DAT but plenty of NET in PFC, dopamine reuptake in PFC occurs primarily through the NET in noradrenergic cells.4

3.1.1.1.1. DAT inhibition via PKC

- AMP possibly inhibits DAT via PKC62

- Several protein kinases regulate DAT function6364

- AMP increases the activity of striatal particulate PKC via a calcium-dependent signaling pathway65

- PKC activation leads to phosphorylation in the N-terminal of the rat striatal DAT66

- PKC activation stimulates DAT-mediated dopamine release62

- PKC inhibitors and the downregulation of PKC62

- Inhibit efflux

- Leave dopamine uptake unchanged

3.1.1.2. Increased release of dopamine (DAT efflux)

The increased DAT efflux increases extracellular dopamine.

Amfetamine drugs release dopamine into the extracellular space 47 5956

Amfetamine therefore not only acts as a dopamine reuptake inhibitor, but also reverses the DAT function so that the DAT not only does not reabsorb dopamine, but also releases it from the cell (efflux).67468

It is certain that amfetamine drugs (drug characteristic: high dose, fast application, fast end of effect) release dopamine from the cell. However, it has not been positively proven that amfetamine drugs (characteristic: drug = low dose, slow release, long-lasting effect) also release dopamine from the cell, and if so, to what extent this occurs.

Empirically, there is no doubt that amfetamine drugs do not deplete dopamine stores, as they would otherwise have no lasting effect.

3.1.1.2.1. Via VMAT2 at high doses

(Only) at a very high dosage as a drug do amfetamines also act on the vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) for dopamine and noradrenaline and then trigger an accumulating release of dopamine from the synaptic vesicles. The high amount of dopamine is then swept out into the synaptic cleft by a reversal of action of the dopamine transporters. This mechanism does not take effect at the usual dosage as an ADHD medication.6 In other words: Amfetamine can enter presynaptic monoamine vesicles and cause an efflux of neurotransmitters towards the synapse.69

An administration of 1 mg/kg AMP (injected) already caused a dopamine DAT efflux that was significantly higher at 10 mg/kg.70

3.1.1.2.2. By increasing intracellular Ca2+

AMP increases intracellular Ca2+, which supports phosphorylation of DAT at the N-terminus of the transporter. Phosphorylation (by CaMKII and possibly also by PKCβ) increases probability of DAT efflux from cytoplasmic DA.71

3.1.1.2.3. Increased DAT efflux via TAAR1

- AMP acts on DAT via TAAR1

Amfetamine enables the trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) to phosphorylate the DAT transporter. This interrupts the reuptake of dopamine and the DAT is stimulated to release dopamine (efflux).69 - AMP also leads to increased intracellular accumulation of DAT72

3.1.2. Vesicular release

- AMP reduces vesicular release because as a lipophilic weak base and as a substrate for VMAT, AMP promotes the redistribution of dopamine from the synaptic vesicles into the cytosol by collapsing the vesicular pH gradient.54 As a result, AMP reduces the number of dopamine molecules released per vesicle.55

- Amfetamine initially reduces VMAT2, while prolonged administration increases it.73 MPH increases VMAT2 per se.7475

- AMP can inhibit vesicular release by indirectly activating D2 autoreceptors. The activation of D2 autoreceptors regulates potassium channels, which in turn regulate the probability of exocytic dopamine release.55

- A computer model determined76

- A maximum release of dopamine at 0.5-1.0 mg/kg AMP (lower at lower doses than at higher doses)

- Most of the dopamine released resulted from AMP-stimulated dopamine neosynthesis

- The dopamine produced was immediately converted into DOPAC, which is excreted extracellularly

- The dopamine was not stored in vesicles

- According to Stahl, AMP does not release dopamine, at least at low doses6

- AMP caused a gradual 10-fold increase in extracellular dopamine in the striatum over approximately 30 minutes in wild-type mice in vitro and in vivo, while simultaneously reducing the dopamine pool available for electrically stimulated release. If vesicular dopamine was previously released into the cytosol by reserpine, extracellular dopamine did not increase; however, AMP caused a rapid increase in dopamine within 5 minutes. In DAT-KO mice, extracellular dopamine did not increase, but at the same time electrically stimulable dopamine release was also reduced. DAT are therefore required for the dopamine-releasing effect of AMP, but not for the vesicle-emptying effect. Dopamine emptying of the vesicles is the rate-limiting step for the AMP effect on dopamine.77

- AMP (10 microm) promoted the release of dopamine from vesicles by reducing the affinity of vesicles for dopamine uptake (from K(m) 0.8 to K(m) 32 microm). However, the amount of dopamine released per pulse was reduced by 82 % (according to another source by 25 to 50 %). The D2 antagonist sulpiride reduced the inhibition of release, i.e. promoted the release. This was reduced in D2-KO mice.

In inhibited D2 autoreceptors, AMP increased the extracellular release of dopamine.53

- Emptying of the vesicular DA stores through a weak alkaline effect on the intravesicular pH gradient. The intravesicular pH gradient is required for the concentration of DA.

- Different effect on release-ready vesicles and reserve pool vesicles:52

- stimulus-dependent effect in the dorsal striatum

- stimulates vesicular dopamine release

- by a firing of short duration

- via vesicle pool ready for release

- Release reduced

- through a firing of long duration

- which accesses the reserve pool

- these opposing effects of vesicular dopamine release were associated with simultaneous increases in tonic and phasic dopamine responses

- stimulates vesicular dopamine release

- in the ventral striatum

- only increased vesicular release and increased phasic signals

- stimulus-dependent effect in the dorsal striatum

3.1.3. D2 autoreceptor activation

Basically, D-amphetamine activates D2 dopamine autoreceptors in the striatum.78

However, drug doses of D-AMP do not cause a significant reduction in dopamine release via activation of the D2 autoreceptors.7980

Since drugs such as levodopa or piribedil show no positive effect in ADHD, although they reduce the firing rate of the dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta, it is doubtful whether the reduction of hyperactivity in ADHD by stimulants is based on presynaptic inhibition. Presumably, the reduction of hypermotor activity by stimulants in ADHD is rather based on an increase in dopamine release.79

3.1.4. Increase in tyrosine hydroxylase

Amfetamine drugs appear to have an activating effect on tyrosine hydroxylase in the dorsal striatum and nucleus accumbens, leading to increased L-dopa levels, but this does not appear to occur via a change in the phosphorylation of tyrosine hydroxylase.81

3.1.5. Increased DA firing / activation in dopaminergic brain regions

3.1.5.1. Increased DA firing in caudate nucleus / putamen (striatum)

High (well above drug dose) D-amfetamine administration (2.5 to 10 mg/kg in the rat into the abdominal cavity), leads to increased dopaminergic firing in the caudate nucleus and putamen and causes focused-repetitive (stereotypic) behavior.8283 The D2 antagonist haloperidol (2 mg/kg) terminates the excessive firing in the caudate nucleus and putamen and the reduced firing in the nucleus accumbens82

3.1.5.2. Increased DA firing in VTA and substantia nigra

D2 antagonists prevent increased firing in the substantia nigra and VTA (in vivo).84

3.1.5.3. Increased activation in the right orbitofrontal cortex, left middle frontal lobe, superior frontal lobe and precentral gyri

Improvement in ADHD symptoms with LDX was associated with significantly increased activation in a number of brain regions previously implicated in reinforcement processing under choice and feedback conditions (e.g., left caudate and putamen, right orbitofrontal cortex, left middle frontal lobe, superior frontal lobe, and precentral gyri).85

3.1.6. Reduced DA firing in the nucleus accumbens

In the nucleus accumbens, 7.5 mg/kg D-Amp led to a reduction in dopaminergic firing.82 The D2 antagonist haloperidol (2 mg/kg) terminated the excessive firing in the caudate nucleus and putamen and the reduced firing in the nucleus accumbens82

3.1.7. Extracellular DA in the striatum increased more than by MPH

Amfetamine increased extracellular dopamine in the striatum of rats by + 1,400 %, four times as much as MPH with + 360 %.86

3.1.8. Synaptic DA binding reduced by AMP in the same way as by MPH

Amfetamine reduced the synaptic binding of dopamine in the striatum in rats and primates to the same extent as MPH (around 25 % reduction).86

3.1.9. DA influence indirectly via effects on dopamine cells emanating from other brain regions

Amfetamine appears to influence the activity of dopamine cells indirectly via its effects on dopamine cells originating in other brain regions.87

Amfetamine can excite dopamine neurons by modulating glutamate neurotransmission. Amfetamine strongly inhibits inhibitory postsynaptic potentials in dopamine neurons mediated by the metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR), but has no effect on excitatory postsynaptic currents mediated by the ionotropic glutamate receptor. Amfetamine desensitizes mGluR-mediated hyperpolarization by:88

- DA release

- Activation of postsynaptic alpha1-adrenergic receptors

- Suppression of InsP3-induced calcium release from internal stores

By selectively suppressing the inhibitory component of glutamate-mediated transmission, amfetamine can promote burst firing of dopamine neurons and thus increase the phasic release of dopamine.

3.1.10. Downregulation of dopamine receptors?

Reports of immediate downregulation of dopamine receptors by administration of amfetamine are based on studies in which rats were given doses of amfetamine. This concerns the dosage level (5, 10, 15 mg/kg for 4 or 20 days twice daily) as well as the form (injection).89 Interestingly, a single dose of D-AMP even increased the number of receptors.8980

So far, we are not aware of any reports of downregulation when administered in the dose and form of medication.

Similarly, only studies with drug doses of amfetamine appear to change the dopamine receptor affinity or receptor status from high affinity to low affinity. Drug doses could alter the balance between receptor status towards low-affinity.80

More on receptor status at High-affinity and low-affinity receptor status In the article Dopamine effect on receptors

However, it is conceivable that amfetamine in drug doses does not cause a desensitization of the postsynaptic or extrasynaptic (the majority of dopamine receptors are located outside synapses) D1 and D2 receptors directly, but via a detour by increasing the extracellular dopamine level. However, this hypothesis has not yet been experimentally proven.80 It is possible that this pathway leads to reduced psychomotor activity through amfetamine medication. In our view, however, this is contradicted by the fact that this effect already occurs with the first dose. On the other hand, this pathway could explain why many people with ADHD benefit from a slow and gradual titration of stimulants.

3.2. Noradrenaline with amfetamine medication

While D-Amp and L-Amp increase extracellular dopamine in the PFC and striatum in a dose-dependent manner, they increase extracellular noradrenaline only in the PFC.4

A: extracellular noradrenaline in the PFC, dose-dependent change due to D-Amp and L-AMP

B: extracellular dopamine in the striatum, dose-dependent change through D-Amp and L-AMP

Source: Heal DJ, Smith SL, Gosden J, Nutt DJ (2013): Amphetamine, past and present–a pharmacological and clinical perspective. J Psychopharmacol. 2013 Jun;27(6):479-96. doi: 10.1177/0269881113482532. PMID: 23539642; PMCID: PMC36661944, published under Creative Commons Attribution License

3.2.1. Noradrenaline reuptake inhibition via NET

- Amfetamine drugs block the dopamine and noradrenaline transporters in a different way to methylphenidate. While the reuptake inhibition of MPH is similar to that of antidepressants, amfetamine drugs act as a competitive inhibitor and pseudosubstrate on dopamine and noradrenaline transporters and bind to the same site where the monoamines bind to the transporter, thereby also inhibiting noradrenalone and dopamine reuptake.5790

- Dextroamfetamine inhibits noradrenaline transporters with moderate efficacy (Ki 39-55 nM).60

- Amfetamine can also stabilize dopamine and norepinephrine transporters in channel configurations, reverse efflux through intracellular vesicular monoamine transporters, and cause internalization of dopamine transporters.61

- D-Amfetamine has about a third of the reuptake inhibition on the noradrenaline transporter (NET) and dopamine transporter (DAT) as racemic methylphenidate.47

- Amfetamine (as well as ephedrine) also inhibits the intracellular noradrenaline transporter, which takes up noradrenaline from the nerve cell into the vesicles (the neurotransmitter stores)90

3.2.2. Noradrenaline release

- Whether amfetamine has a noradrenaline-releasing effect when administered as a drug is the subject of controversial debate, as is the case with dopamine. There are voices against6 as well as in favor.5659

- D-Amfetamine secondarily increases the release of noradrenaline.78 This is always the case with dopaminergic drugs due to the conversion of dopamine (approx. 5 to 10 %) into noradrenaline.

- There is no doubt that amfetamine medication does not lead to a chronic depletion of noradrenaline reserves in the sense of a deficiency state. It is empirically proven that amfetamine medication for ADHD does not lead to long-term habituation effects

2.5 mg/kg AMP in mice:91

- stereotypical behavior (a sign of strongly increased extracellular dopamine); as strong as 20 mg/kg MPH

- extracellular dopamine increased

- extracellular noradrenaline increased

- extracellular serotonin increased

3.2.3. Reduction of noradrenaline metabolites only in responders

- Several independent studies have found that D-amfetamine drugs reduce the urinary metabolite of noradrenaline, MHPG. The decrease in urinary MPHG is thought to be an important indicator of stimulant onset, indicating a lowering of noradrenaline levels by dextroamfetamine drugs.92](https://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/1982-21744-001)

- Furthermore, the reduction in noradrenaline metabolites only occurs in people with ADHD who respond positively to dexamfetamine (responders).93

- Even with the administration of methylphenidate, only the responders showed a significant decrease in MPHG in the urine, while MPHG in the urine of the non-responders did not decrease.94

The authors conclude that the level of noradrenaline in ADHD is reduced. - Furthermore, in several studies with people with ADHD, it was found that behavioral improvements were proportional to the reduced noradrenal metabolite levels (using D-amfetamine medication).95

In contrast to the reduction of metabolites in urine by D-amfetamine, the noradrenaline increase in the PFC mediated by D-amfetamine is about as pronounced as that of MPH, but significantly more dose-dependent and therefore more controllable.47

3.2.4. DA firing and DA bursting increased via noradrenaline α1 receptors

D-Amp (1 to 2 mg/kg) acts via alpha1-adrenoceptors96 (but not via alpha2- or beta-adrenoceptors) to increase dopaminergic firing and bursting in substantia nigra and VTA (in vivo). This adrenergic pathway is usually masked by the reduction in dopaminergic firing mediated by D2 autoreceptors and is visualized by D2 antagonists or by simultaneous administration of D1/D5 and D2/D3/D4 blockers. The selective norepinephrine uptake blocker nisoxetine did not increase the DA firing rate, but did increase DA bursts.8497

D-amfetamine appears to activate the noradrenaline α1-receptor in the PFC, as the α1-receptor antagonist prazosin completely neutralized the effect of D-amfetamine in the PFC. In contrast, D-amfetamine does not appear to target either the α2 receptor or the β receptor, as the effect of D-amfetamine persisted when the α2 or β receptors were blocked.98

D-amfetamine promotes the up-state of cortical neurons by activating99

- Central α1A-adrenoceptors

- D1 receptors

- D2 receptors

- But not by D1 or D2 receptors alone

In contrast, the dopamine/noradrenaline precursor L-DOPA did not promote the up state.

Arousal is associated with an increased up state, while slow-wave sleep, general anaesthesia and calm wakefulness are characterized by an oscillating change between up and down states. During arousal, the down states end and the up/down oscillation changes to a sustained up state.

The up/down oscillations appear to be relevant for memory consolidation, while the transition to a sustained up state is required for arousal and attention.99

3.3. Monoamine

3.3.1. Monoamine degradation inhibition via MAO

Amfetamine medication acts - albeit rather weakly4 - as an MAO inhibitor,10048 unlike low-dose MPH. Whether high-dose MPH acts as an MAO inhibitor is unknown.47

MAO is an enzyme that breaks down dopamine and noradrenaline in the cell. MAO inhibitors thus increase the amount of dopamine and noradrenaline available in the cell. As dopamine and noradrenaline continue to be synthesized in the nerve cell, the noradrenaline and dopamine levels in the cell continue to rise. This leads to a reversal of the effect of the transporters (which actually return DA and NE from the synaptic cleft into the cell), so that they release NE and DA into the synaptic cleft, even without this being triggered by a nerve signal to be transmitted.100 This effect triggers peripheral hypertension and an increase in heart rate. As this mechanism of action occurs indirectly at the presynapse, ephedrine and amfetamine drugs are also called “indirect sympathomimetics”, while active ingredients that act directly at the postsynaptic receptors are called sympathomimetics.100

3.3.2. Monoamine release

Dextroamfetamine increases monoamine release from presynaptic terminals101, possibly via interaction with vesicular monoamine transporter 2 and reversal of plasma membrane monoamine transporters.60

3.4. Serotonin

3.4.1. Serotonin reuptake inhibition

Dextroamfetamine also inhibits serotonin transporters (Ki 1.4-3.8 μM) to a small extent.101

3.4.2. Serotonin release

Amfetamine medication is said to release a small amount of serotonin.1025 Here too, it is unclear whether this is really the case even when dosed at drug level, or whether this effect is only limited when dosed as a drug. In any case, Stahl does not report a serotonergic effect of amfetamine drugs.57

2.5 mg/kg AMP in mice:91

- stereotypical behavior (a sign of strongly increased extracellular dopamine); as strong as 20 mg/kg MPH

- extracellular dopamine increased

- extracellular noradrenaline increased

- extracellular serotonin increased

Serotonin release through amfetamine drugs

Amfetamine drugs (MDMA, MBDB) also increase the release of serotonin. It is assumed that amfetamine-induced serotonin release not only influences psychomotor activation, but also subjective well-being (and euphoria when taken as a drug).103 MDBD causes almost no dopamine release.

Hyperactivity induced by 5 mg or 10 mg/kg MDMA (= 10 to 20 times higher dosage than as a drug) could be prevented by prior administration of 2.5 and 10 mg/kg of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor fluoxetine. Fluoxetine had the same effect on the interactive effect of MDMA and P-chloroamfetamine.104 This suggests that MDMA causes hyperactivity by increasing serotonin via the serotonin transporter, which was blocked by fluoxetine as a serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

- There is evidence that an increased release of serotonin indirectly increases dopamine levels.104

- Other sources indicate a serotonin-increasing effect of amfetamine salts due to inhibition of monoamine oxidase.8

- Amfetamine increases c-Fos expression in the mPFC, striatum and nucleus accumbens. A serotonin 1A receptor agonist reduced the c-Fos increase in the mPFC and striatum, but not in the nucleus accumbens.105

- MPH itself has an agonistic effect on the 5-HT1A receptor.48

3.5. Effect on the HPA axis

3.5.1. ACTH increased

Lisdexamfetamine and d-amfetamine significantly increased ACTH plasma levels in healthy subjects.106

3.5.2. Corticosteroids increased

- D-amfetamine drugs such as lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) increase cortisol levels, but not testosterone levels.106

- The following were increased

- Glucocorticoids (as with methylphenidate; the increase was even greater with the drugs MDMA or LSD)

- Cortisol

- Cortisone

- Corticosterone

- 11-Dehydrocorticosterone,

- 11-Deoxycortisol

- Glucocorticoids (as with methylphenidate; the increase was even greater with the drugs MDMA or LSD)

- The following remained unchanged

- Mineralocorticoids

- Aldosterone

- 11-Deoxycorticosterone

- Mineralocorticoids

The increase in the cortisol level causes a stronger addressing of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR) by cortisol. Cortisol causes the HPA axis to be switched off again via GR at the end of the stress response.

In ADHD-HI and ADHD-C (both with hyperactivity), due to the flattened endocrine stress response of the adrenal gland, it can be assumed that the GR are not sufficiently addressed to switch off the HPA axis again after a stress reaction. In addition, in ADHD-HI (unlike ADHD-I) there is often deficient GR function, which makes HPA axis deactivation even more difficult.

Find out more at Medication for ADHD at ⇒ Dexamethasone for ADHD. If the release of cortisol is now increased by AMP, this could improve the resilencing of the HPA axis in ADHD-HI. However, as AMP also works in ADHD-I, the primary mechanism of action is likely to be different.

3.5.3. Increased steroid hormones

Lisdexamfetamine and d-amfetamine significantly increased the plasma levels of, among others, in healthy subjects:106

- Androgens

- Dehydroepiandrosterone

- Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate

- Androstenedione (Δ4-androstene-3,17-dione)

- Progesterone (only for men)

The androgen remained unchanged

- Testosterone

Since aggression correlates with an increased testosterone to cortisol ratio, amfetamine drugs have an anti-aggressive effect due to the relative increase in cortisol levels.

More on this at ⇒ Neurophysiological correlates of aggression

A study in adolescent rhesus monkeys found that both active ingredients increased testosterone levels, MPH even more than AMP, as a consequence of 12 months of AMP or MPH administration in drug doses.107 Another study in rhesus monkeys found reduced testosterone levels with MPH administration.108

A reduction in testosterone levels was observed in rodents after administration of amfetamine.109110

3.6. Inhibition of OCT2

Basic information on uptake-2 transporters can be found at Dopamine degradation by organic cation transporters (OCT) In the article Dopamine reuptake, dopamine degradation

Organic cation transporter 2 (OCT2) is involved in the degradation of dopamine. OCTs take up dopamine and noradrenaline as well as serotonin and, to a somewhat greater extent, histamine in glial cells, where they are broken down by COMT. OCT2 and OCT3 are also located on (also dopaminergic) neurons.

While methylphenidate only binds to OCT1 (IC50: 0.36) and neither to OCT2, OCT3 nor PMAT111, d-amfetamine acts as a highly effective hOCT2 reuptake inhibitor (Ki: 10.5 mM) and moderately effective hOCT1 reuptake inhibitor (Ki: 202 mM), while it only interacted with hOCT3 from 100 μM (Ki: 460 mM) (hOCT: human OCT).111112

d-Amfetamine binds approximately equally strongly to hOCT2 and hOCT3 and to these by an order of magnitude (factor 10) weaker than to DAT112

Binding of amfetamine to OCT may contribute to cellular and behavioral effects of amfetamine.112

OCT2 reuptake inhibitors have an antidepressant effect.113 In addition, even much lower doses of venlafaxine or reboxetine have an antidepressant effect in OCT2-KO mice than in wild-type mice114

We think it is worth considering whether this approach could also support the effect of dopamine reuptake inhibitors in ADHD.

These correlations could also explain why AMP, which also acts as an OCT2 inhibitor, has a better antidepressant effect than MPH, which only binds to OCT1.

3.7. Other effects on brain functions

- D-Amfetamine increases metabolism in the right caudate nucleus and decreases it in the right Rolandi region and in the right anterior inferior frontal regions.115

- Neuroprotective effect in case of stroke or traumatic brain injury

- D-amfetamine (like L-dopa, which has no effect on ADHD, although it has a dopaminergic effect) is also suitable for restoring brain function after strokes, but only if appropriate training measures are taken at the same time.116 D-amfetamine increases dopamine, which has a neurotrophic effect (promotes neuroplasticity). Dopaminergic drugs such as (D-)amfetamine drugs or MPH can therefore also support appropriate training measures (e.g. neurofeedback, cognitive behavioral therapy) in ADHD by reducing the restrictions on learning ability.

- Low-dose methamfetamine given within 12 hours of a stroke or traumatic brain injury was neuroprotective and improved cognitive abilities and functional behavior.117

- There are similar reports with regard to MPH, although it also seems to depend on the rapid administration after the craniocerebral trauma118

- Methylphenidate and amfetamine drugs increase the power of alpha (in rats), while atomoxetine and guanfacine do not.119

- Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) has the following effects120

- Increased acetylcholine levels in the cortex

- Increased histamine levels in the cortex and hippocampus (which escitalopram given in parallel only prevents in the hippocampus)

Amfetamine medication is therefore not just a substitute for methylphenidate, but has its own area of application.

3.8. Overview of AMP and neurotransmitters

3.8.1. Binding affinity of AMP, MPH, ATX to DAT / NET / SERT

The active ingredients methylphenidate (MPH), d-amfetamine (d-AMP), l-amfetamine (l-AMP) and atomoxetine (ATX) bind with different affinities to dopamine transporters (DAT), noradrenaline transporters (NET) and serotonin transporters (SERT). The binding causes an inhibition of the activity of the respective transporters.121

The values given in the following table by Easton et al. refer to values in the synaptosome as well as to the DAT in the striatum and the NET in the PFC.

| Binding affinity: stronger with smaller number (KD = Ki) | DAT | NET | SERT |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPH | 34 - 200121 , 34124 | 23824, 339121 | > 10,000121 |

| d-AMP (Vyvanse, Attentin) | 34 - 41121 , 206 (sulphate) 24 | ** 23.3 - 38.9**121 , 54.8 (sulphate)24 | 3,830 - 11,000121 |

| l-AMP | 138121 , 1435 (sulphate) 24 | ** 30.1**121 , 259 (sulphate)24 | 57,000121 |

| ATX | 1451 - 1600121 235524 | ** 2.6 - 5**121 , 20.624 | ** 48 - 77**121 |

| GBR-12909 | 40.224 | ||

| Desipramine | 4.924 |

3.8.2. Effect of AMP, MPH, ATX on dopamine / noradrenaline per brain region

The active ingredients methylphenidate (MPH), amfetamine (AMP) and atomoxetine (ATX) alter extracellular dopamine (DA) and noradrenaline (NE) to different degrees in different regions of the brain. Table based on Madras,121 modified.

| PFC | Striatum | Nucleus accumbens | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPH | DA + NE (+) |

DA + NE +/- 0 |

DA + NE +/- 0 |

| AMP | DA + NE + |

DA + NE +/- 0 |

DA + NE +/- 0 |

| ATX | DA + NE + |

DA +/- 0 NE +/- 0 |

DA +/- 0 NE +/- 0 |

4. Effect of amfetamine medication compared to MPH / atomoxetine

In MPH nonresponders, lisdexamfetamine (EU: Vyvanse) and atomoxetine were compared in a randomized double-blind study with n = 200 subjects. Lisdexamfetamine was significantly more effective than atomoxetine in 2 of 6 categories and in the overall assessment.122

Lisdexamfetamine (EU: Vyvanse) also had a good effect on comorbid depression symptoms in a double-blind study.123 MPH is not known to have any positive effects on depression symptoms.

A 2-year study in children and adolescents (n = 314) showed a responder rate of between 70 and 77 % with good efficacy and manageable side effects.124

5. Effect on ADHD symptoms

In people with ADHD who respond positively to D-amfetamine medication as well as MPH, the effect of D-amfetamine medication is at least on a par with MPH125, in our experience even significantly better in adults.

For a comparison of the effectiveness of individual medications and forms of treatment, see ⇒ Effect size of different forms of treatment for ADHD.

According to the current European consensus, amfetamine medication is the first choice ADHD medication for adults (before methylphenidate), and the second choice for children (after methylphenidate).4546

Amfetamine medication should also always be tried if MPH does not work (non-responder).

5.1. ADHD-I (without hyperactivity)

MPH has a stronger activating and drive-enhancing effect on most people with ADHD than AMP medication. Contrary reports126 are not consistent with our experience.

Statements in the specialist literature that amfetamine medication is more suitable for people with ADHD-I than MPH, partly because people with ADHD-I are above-average AMP nonresponders,127 cannot be confirmed from our experience either

We know several persons with ADHD-HI who are significantly better helped by amfetamine medication than MPH and people with ADHD-I who cope better with MPH. We are not aware of any subtype-specific effect of amfetamine medication or methylphenidate. In our experience, amfetamine medication works just as well for ADHD-HI as for ADHD-I.

5.2. Attention control

People with ADHD have a reduced extrinsic and intrinsic motivational capacity. For example, they need higher rewards to be as motivated for something as non-affected people. However, once motivation is awakened in persons with ADHD, their attention and controllability can no longer be reliably distinguished from that of non-affected people. ⇒ Motivational shift towards own needs explains regulation problems

Attention correlates with a deactivation of the default mode network (DMN), among other things. Stimulants are able to align the attentional control of people with ADHD (or the motivational capacity, from which attention follows) with that of non-affected people, which is then also shown by a normalization of DMN deactivability.128

More on the deviant function of the DMN in ADHD and its normalization by stimulants, including further references at ⇒ DMN (Default Mode Network) In the article ⇒ Neurophysiological correlates of hyperactivity.

The cited references refer to the effect of methylphenidate. However, it can be assumed that the effect is achieved by stimulants in general.

People with ADHD report that MPH allows for greater focus, while amfetamine medication (Vyvanse) tends to create a more relaxed general alertness and has a slightly more pleasant effect overall.

5.3. Comorbid depression or dysthymia

Amfetamine medications probably also have a mild serotonergic effect and thus have a special area of application in comorbid dysthymia or depression, especially since serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can have adverse effects in ADHD (especially ADHD-I) (see there).

In forums, a number of people with ADHD report a significant antidepressant effect of amfetamine medication, which they are not familiar with from MPH.129 This is consistent with the experiences of users known to us.

As amfetamines can have a stronger drive-increasing effect than MPH, this can release an existing suicidal tendency that was not previously carried out due to the existing depression. Amfetamine medication should therefore be used with caution in cases of (even hidden) severe depression.

Attention: A supposed dysthymia (mild chronic depression) in people with ADHD must be clearly differentiated from the original ADHD symptom of dysphoria during inactivity.

Find out more at ⇒ Depression and dysphoria in ADHD In the section ⇒ Differential diagnosis of ADHD.

5.4. Comorbid anxiety disorders / depression

Comorbid anxiety disorders or depression can be exacerbated by stimulants, as anxiety and moods are regulated by the dopaminergic activity of the ventromedial PFC in conjunction with the limbic system.57

5.5. Comorbid sleep disorders

Amfetamine medication has a very long duration of action (up to 13 hours). Taking it too late (less than 14 hours before going to bed) could therefore cause problems falling asleep. On the other hand, some people with ADHD report feeling pleasantly tired in the evening and that they no longer have problems falling asleep.

Studies show that amfetamine medication improves overall sleep quality in ADHD.130131

5.6. Impulsiveness

People with ADHD reported in forums that MPH worked better against impulsivity than Vyvanse (lisdexamfetamine).132

6. Response rate (responding / non-responding)

Response here means whether there is an effect on the ADHD symptoms. People with ADHD who do not respond sufficiently to a medication are called non-responders.

Non-responding does not mean having no effect, but merely that the effect remains below the level of symptom improvement specified in the respective study.

One study reported a responder rate of 80% (defined as an improvement of more than 30% in ADHD-RS-IV scores and greatly or very greatly improved CGI-I scores)133

A summary of several studies reports a 69% response rate to amfetamine medication and a 59% response rate to methylphenidate. 87% of people with ADHD responded to one of the two types of medication.2

A 2-year study of L-amfetamine medication in children and adolescents (n = 314) showed a responder rate of between 70 and 77% with good efficacy and manageable side effects.124

For MPH non-responders, it is therefore highly recommended to test a medication with amfetamine drugs (see 1.2.), and vice versa.

According to a Cochrane study, all amfetamine drugs work equally well in adults.134 As the studies evaluated in this study did not examine the effect of LDX and dAMP on the same people, the Cochrane meta-analysis can only make statements about the statistical response rate of the various active ingredients per se, and nothing about whether different AMP active ingredients work differently for individual people with ADHD.

There are reports that dextroamfetamine sulphate can be helpful for individual persons with ADHD for whom LDX did not work (well) or for too long. This is also indicated in a leaflet that describes the parameters to be considered when switching from LDX to dAMP.135

In addition, there are increasing reports in practice that different lisdexamfetamine preparations can (but by no means have to) show considerable intraindividual differences. This also applies to people with ADHD who had not previously thought that there could be differences, or who were convinced that the products were completely interchangeable. Some people with ADHD reported that they were able to reliably reproduce differences in effect by switching between different preparations on a daily basis. There is no pharmacological explanation for this.

In carriers of the COMT Val-158 Met gene polymorphism, amfetamine increased the efficiency of the PFC in subjects with presumably low levels of dopamine in the PFC. In contrast, in carriers of the COMT Met-158-Met polymorphism, amfetamine had no effect on cortical efficiency at low to moderate working memory load and caused deterioration at high working memory load. Individuals with the Met-158-Met polymorphism appear to be at increased risk for an adverse response to amfetamine.136

7. No gender-specific differences in effectiveness

Amfetamine medications do not appear to show any gender-specific differences in effect.137

8. Calming effect at low doses, activating at high doses

D-Amfetamine appears to have a biphasic action profile. Low doses of 0.5 to 1 mg/kg in rats (equivalent to about 0.2 to 0.6 mg/kg in humans) reduce (hyper)activity, while higher doses increase it.51

9. Dosage of amfetamine medication or MPH

About 66% of all persons with ADHD respond equally well to MPH as to amfetamine medication.

22% respond better to amfetamine medication than to MPH.

11% respond better to MPH than to amfetamine medication.138

Around 15% of people with ADHD respond best to the active ingredient D-Amfetamine.139

According to this result, it would make more sense to first try therapy with amfetamine medication and only try MPH as a second option in the event of non-response, as people with ADHD respond somewhat better to amfetamine medication than to MPH.

Highly gifted people with ADHD (here: IQ > 120) are said to respond better to amfetamine medication than less gifted people with ADHD.140

An interesting study discusses the effectiveness of lisdexamfetamine.141

It is advisable to start with a very low dosage, which is then slowly increased. Even if the optimal dosage were known, an immediate optimal dosage would possibly lead to excessive demands.142 The symptoms of ADHD are caused by signal transmission problems between the brain nerves because the neurotransmitter level (dopamine, noradrenaline) is too low. An optimal neurotransmitter level corrects the signal transmission problems. If the neurotransmitter level is too high due to an overdose, signal transmission is just as impaired as if the level is too low.

This explains why low doses should be given at the beginning and then, with persistent persistence, higher doses should be given until a worsening of symptoms is observed.

As the number of dopamine transporters in adults is half that of 10-year-olds, it is advisable to start with a much lower dosage than in children.

10. Effect profile (temporal) / duration of action

In replicated studies on the duration of action of amfetamine drugs, children had a shorter half-life of around 7 hours, while adults had a longer half-life of around 10 to 12 hours143

The time course of the effect (effect profile) depends less on the active ingredients than on the specific composition of the medication.

Vyvanse has a very elongated effect profile without pronounced peaks, so that barely any flooding or rebound effects are noticeable. See: Graphic representation of the Vyvanse effect profile. However, the graph from Shire’s patent application refers to the plasma level in rats at an extremely high dose of 3 mg/kg.

Another graph shows the The progression of the active substance at 30 mg, 50 mg and 70 mg Vyvanseon page 20.

The extent to which the binding of D-amfetamine to lysine in lisdexamfetamine really leads to a flattened and prolonged concentration of amfetamine in the blood plasma remains to be seen. A single dose of 40 mg D-amfetamine or 100 mg lisdexamfetamine (above the medically advisable doses) in healthy people showed no relevant differences in the amfetamine blood plasma concentration.144 Furthermore, the study data probably indicate a subjective impression of a gentler and longer effect of lisdexamfetamine on the part of the test subjects, although this is not reported by the authors. A further limitation of the study is that the test subjects were treated with a single dose and there was no dosing to the tested dosage. The authors themselves cite studies that show that amfetamine medication requires familiarization phases or (initial) habituation effects. The results of the study are therefore primarily of pharmacological interest, but only of limited practical use.

Empirically, adults report quite unanimously of a gentler and prolonged effect of lisdexamfetamine. The majority cite 5 to 7 hours as the duration of action of a single dose. There is also a fairly unanimous report of a very slow onset of action, with 1 to 2 hours being mentioned in most cases.

An internal (and not representative) Survey at adhs-forum.adx.org on the duration of action of Vyvanse (n = 80) and another survey in a sub-reddit on Vyvanse (n = 467) yielded the following result (n = 547):

| Duration of action of a single dose of Vyvanse | % of participants |

|---|---|

| 5 hours and less | 40.8 % |

| 6 to 7 hours | 26.7 % |

| 8 to 9 hours | 15.4 % |

| 10 to 11 hours | 11 % |

| 12 hours and more | 6.2 % |

The surveys are not representative (no consideration of age, weight, dose level or gender), but clearly show that a duration of action of 13 or 14 hours, as stated by the manufacturer, is only exceptionally achieved in adults in practice.

A more detailed Survey on the single-dose duration of action of all ADHD medicationswhich also includes the aforementioned secondary factors, has been running since March 2023 and could show initial results in fall 2023.

Many people with ADHD (we know of dozens of cases from the forum) take 2 or 3 single doses of Vyvanse per day to achieve the required all-day coverage, even if this does not comply with the manufacturer’s instructions. The individually shortened duration of action could also be a consequence of a low dosage of often 30 mg or less per single dose, which was chosen when an overdose was perceived at a higher single dose during the phase of high D-AMP blood plasma levels. In almost no person with ADHD does the sum of the single doses exceed 70 mg / day.

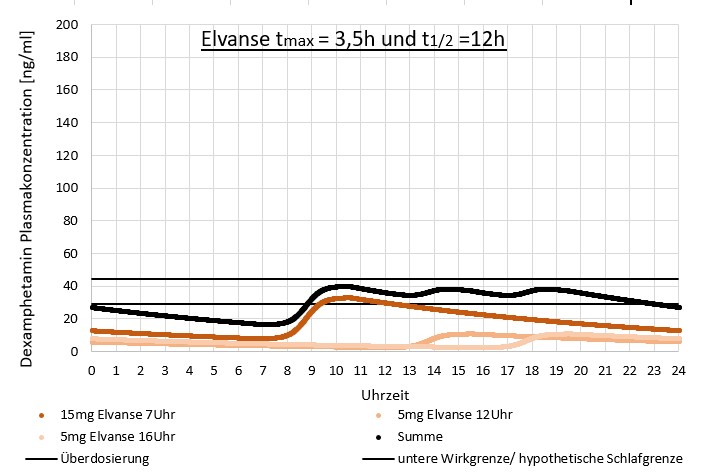

The result of taking multiple smaller doses of Vyvanse on D-AMP blood plasma levels could (hypothetically) look like this:

11. Areas of application of amfetamine medication in relation to MPH

According to the current European consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults, amfetamine medication is the first choice of medication for ADHD in adults (before methylphenidate), and the second choice of medication for children (after methylphenidate)4546

In children who are MPH non-responders, i.e. who do not respond to MPH, the efficacy of amfetamine medication should be tested.

Persons with ADHD with pronounced dysphoria during inactivity or with comorbid depression benefit particularly from amfetamine medication.

In addition, people with ADHD who require stronger activation may be able to cope better with amfetamine medication.

Highly gifted people are said to respond better to amfetamine medication than to MPH.140

12. Side effects

An evaluation of the reports to the WHO VigiAccess database revealed the following relative frequency of adverse reaction reports for dextroamfetamine (the % figures do not indicate the frequency of occurrence during use):145

| Reporting rate % | Side effect |

|---|---|

| 4.3 % | Unexpected therapeutic response |

| 3.08 % | Headache |

| 1.96 % | Depressive mood |

| 1.86 % | Fatigue |

| 1.74 % | Insomnia |

| 1.68 % | Nausea |

| 1.67 % | Palpitations |

| 1.64 % | Attention deficit disorders |

| 1.43 % | Anxiety |

| 1.35 % | Dizziness |

| 1.16 % | Drowsiness |

| 1.15 % | Decreased appetite |

| 1.13 % | Irritability |

| 1.03 % | Discomfort |

| 0.94 % | Unrest |

| 0.9 % | Dry mouth |

| 0.83 % | Aggressiveness |

| 0.8 % | Excitation |

4.84% of the reports concerned an ineffectiveness of the drug, 1.75% a problem with product substitution.

The evaluation does not distinguish between sustained release and immediate release AMP or AMP in prodrug form (lisdexamfetamine). Sustained release / prodrug medications have a lower side effect profile.

12.1. No liver damage with normal medication dosage

High doses of amfetamines may be associated with liver damage and certain forms of clinically apparent liver damage. This is most commonly reported with methylenedioxymetamfetamine (MDMA: “ecstasy”).146

Amfetamine drugs, on the other hand, are dosed so low that this does not occur: the dose makes the poison. See also under ⇒ Stimulants as medication versus stimulants as drugs.

12.2. AMP increases histamine

AMP increases histamine,147148 as do all other known ADHD medications:

- Atomoxetine

- Methylphenidate

- Modafinil

- Nicotine

- Caffeine

This is why people with histamine intolerance often have problems when taking ADHD medication.

A person with ADHD with histamine intolerance reported that she could not tolerate AMP and sustained release MPH at all, but could tolerate immediate release MPH in small doses.

12.3. No increased cardiovascular risks

Several large studies found no increased risk of serious cardiovascular events such as stroke, heart attack or cardiac arrhythmia for amfetamine drugs.149150

A study over 14 years found a 4% increase in the risk of cardiovascular problems per year of taking stimulants (methylphenidate, amfetamine medication) and, to a lesser extent, the non-stimulant atomoxetine.151

According to a meta-analysis, daily use of amfetamine medication had the following effects152

- systolic blood pressure increased by 1.93 mmHg (k = 56 RCT, n = 10,583)

- diastolic blood pressure increased by 1.84 mmHg (k = 56 RCT, n = 10,583)

- Heart rate increased by 3.71 beats per minute (k = 47 RCT, n = 10,075)

12.4. Individual cases of trichotillomania

Individual cases of trichotillomania (pulling out hair) have been reported.153 Trichotillomania is a specific form of impulse control disorder.

12.5. Erection, libido, reproduction

The package insert for Vyvanse mentions erectile dysfunction in 1 to 10 out of 100 men. However, the specialist literature or studies do not report any sexual impairments caused by amfetamine medication.

Reports from the ADxS-ADHD forum sometimes report erection problems with amfetamine medication, but barely with MPH.

Two male persons with ADHD reported a loss of sensitivity in the genital area after consuming red wine outside the active period of the regularly taken Vyvanse. In one of the persons with ADHD, low nicotine consumption outside the active period is another suspicious factor.

A single case report documented a reduction in testosterone and other sex hormones and a reduction in sperm count with an amfetamine drug, which was reversed by switching back to MPH.154

Amfetamine drugs also bind to alpha1-adrenoceptors (see above).

A blockade of alpha1-adrenoceptors leads to a delayed detumescence of the erectile tissue and thus to a reduced ability to ejaculate and orgasm, both in women and in men.155 Blockade is the opposite of binding. Dopamine agonists such as L-dopa or bromocriptine cause an increase in sexual desire and sexual activity.

Amfetamine (usually associated with drug use) can alter spermatogenesis and lead to oxidative stress and subsequent apoptosis in testicular tissue156

Amfetamine in drug doses (here: lisdexamfetamine) did not change the testosterone level.157

Amfetamine (in drug doses) is able to reduce testosterone production in rodents and increase the formation of cyclic AMP in the testicles156

A single intravenous injection of amfetamine (administered as a drug) reduced hCG-stimulated testosterone release. The LH plasma level remained unchanged.

Amfetamine thus appears to have a direct and dose-dependent effect on Leydig cells, where it inhibits testosterone production by activating adenylate cyclase.109

A single intraperitoneal administration of methamfetamine initially lowered serum testosterone and increased it to a level above baseline after 48 hours.158

Chronic high methamfetamine administration reduced testosterone159 and increased GABA in the testes.160 GABA is involved in the proliferation of Leydig cells and testosterone production.

MDMA inhibits the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in male rats. Acute and chronic MDMA administration resulted in decreased serum testosterone and GnRH mRNA expression. LH, progesterone and oestradiol remained unchanged. This indicates a reduced drive by hypothalamic GnRH neurons as a cause of inhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.161

Subcutaneous MDMA administration for 12 weeks on three consecutive days/week (simulating human weekend use) did not alter the hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.162

Methamfetamine can trigger apoptosis in testicular germ cells of mice163164 and reduce sperm count.165

Rats receiving 5 ml/kg methamfetamine intraperitoneally for 7 and 14 days (drug dose) showed significantly decreased spermatogonia, primary and secondary spermatocyte counts and spermatogenesis indices (tubule differentiation index, spermiogenesis index, repopulation index and mean testicular tubule diameter).166

MDMA is also capable of inducing histological changes in the testicles of rats and causing DNA damage to the sperm in a dose-dependent manner. However, the sperm count increased and the spermatid count decreased.162 MDMA increased the body temperature and the immunoreactivity of heat shock protein 70 (HSP70), which could activate apoptosis in the testicular tissue of the rat.167

A pilot study in men with sexual problems reported improvements in the subjective sexual experience (reduced time to orgasm or increased frequency of orgasm) with 5 to 20 mg of amfetamine salts (Adderall) 1 to 4 hours before sexual activity (up to 10 doses/month)168

In 5 individual cases, the resolution of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction by low doses of dextroamfetamine or methylphenidate was reported.169 Further case studies report multiple erections (15-year-old), hypersexual behavior (8-year-old) due to OROS-MPH (Concerta)170 and priapism (14-year-old).171

One study reported a doubled rate of testosterone deficiency in adult persons with ADHD after 5 years of stimulant use (1.2%) compared to persons with ADHD without stimulant use (0.67%) or non-stimulant use (0.68%).172

12.6. Amfetamine medication for the elderly

There are only a few studies on the effect and safety of amfetamine medication in older people.

One study found no increased risks for lisdexamfetamine in people between 55 and 84 years of age. There were no age-related trends in pulse or blood pressure changes and the safety profile of LDX was identical to that observed in younger adult study participants. The clearance of LDX decreased with age, so that a low dosage is reasonable or a prolonged effect can be expected.173

This is consistent with our known experience with stimulants in older people with ADHD. Nevertheless, particularly careful observation of the development of blood pressure is recommended.

12.7. Other

Common side effects of amfetamine mixed salts are:27

- Loss of appetite

- Mood swings

Rare serious side effects of amfetamine mixed salts are:27

- psychotic symptoms

- Seizures

- Risk of abuse

The drug MDMA (unlike amfetamine drugs) can damage nerve cells and attack the blood-brain barrier.174

12.8. Overdose

Symptoms of a (severe) overdose of amfetamine (in the sense of poisoning) include

- Agitation175

- Hyperactivity176

- Movement disorders175

- Tremor175

- Hyperthermia176

- Tachycardia (rapid heartbeat)176

- Tachypnea (increased respiratory rate)176

- Mydriasis (pupil enlargement)176175

- Trembling176

- Seizures176, in extreme cases up to epileptic forms175

- Hyperreflexia (excessive reflex response)175

- combative behavior175

- Confusion175

- Hallucinations175

- Delirium175

- Fear175

- Paranoia175

It is hardly surprising that doses of 11.3 mg / kg LDX trigger toxic effects in rats, as this is significantly higher than drug doses.177

13. Degradation of amfetamine

13.1. Degradation of LDX to d-AMP

Lisdexamfetamine (Vyvanse) is converted to d-AMP in the blood cytosol of erythrocytes by an unknown amino acid (probably an aminopeptidase)178179 by cleaving the covalent bond between d-amfetamine and L-lysine. Only d-AMP is pharmacologically active. d-AMP is predominantly degraded renally, the rest presumably via CYP2D6.

96% of LDX is excreted in the urine, of which18

- 42 % of the dose as AMP

- 25 % as hippuric acid

- 2 % as intact LDX.

In contrast to AMP, LDX is less sensitive to changes in urine pH.

The half-life of LDX is typically less than 1 hour.

13.2. Degradation of D-AMP and L-AMP

Dextroamfetamine is said to have a half-life of

- about 7 hours180

- 9-11 hours

Taking it together with a high-fat meal can extend the half-life of d-AMP by one hour.

A half-life of 11-14 hours is reported for l-Amp.

Two online surveys of around 550 people with ADHD who take lisdexamfetamine showed that around 40% have a single-dose duration of action of 5 hours or less and two-thirds have a single-dose duration of action of 7 hours or less. More on this under Effect and duration of action of ADHD medication